Crime, Culture and Social Control

25/2017

ISBN 978-9985-870-39-6

Issue

Bringing about Penal Climate Change: The Role of Social and Political Trust and of Perceptions about the Aims for Punishment in Lowering the Temperature of Punitiveness

The paper presents a study demonstrating that social and political trust are good predictors of punitive attitudes. People who have low generalised social trust and low political trust would impose longer sentences on offenders. Awareness of the aims behind punishment is a strong predictor of systematically severe punitive attitudes – those for whom the aims for punishment revolve around the protection of society (rather than focusing on reforming the offender) are more punitive. The study indicates that penal attitudes are best altered in a trusting environment, and that attempts to achieve a shift away from harsh ones should be targeted principally at the most punitively minded groups in the relevant society. The assumption is that in an environment where penal attitudes towards offenders are milder, major changes in crime policy such as introduction of individualised penalties, reduction in prison terms and population would be more easily achieved.

Keywords:

Punitiveness; political trust; social trust; aims in punishment

1. Introduction

The purpose for this article is to analyse factors that are related to the public’s punitiveness. Much of the discussion is based on data from an Estonian public poll, which makes it a novel contribution in several respects. With few exceptions *1 most studies on public punitiveness have thus far been conducted in Anglo-American countries where penal populism is a recognised phenomenon. In Estonia, the social environment is different and penal policy is rarely used to focus attention in election campaigns. At the same time, the importance of public opinion in penal policy formulation should not be underestimated. In the penal field, public opinion primarily influences policy-making by calling for the adoption of legislation that is tough on crime and for allocation of further resources to law enforcement. In its milder forms of appearance, public opinion makes politicians averse to initiatives aimed at softening penal laws. Reactionist provisions that more often than not represent stop-gap solutions due to panic-provoking events (e.g., a murder case with extensive media coverage) are a good example of public opinion’s influence on penal policy-making. Needless to say, harsh punishments have not proved an effective tool against crime, as harsh measures destabilise society *2 .

For many years, Estonia has struggled with high incarceration rates *3 and has searched for avenues to bring the number of inmates down. Imprisonment rates have been shown to depend more on policy choices than on actual crime rates *4 , which means that reduction of the number of prisoners has to be a deliberate policy choice, unlikely to be achieved as a side-effect of the fight against crime. Changes in the legislation concerning parole release have allowed Estonia to reduce the number of prisoners by approximately 1,000 over five years but now appear to have exhausted their potential. Other examples of steps that governments have taken to bring down the number of inmates include reducing the capacity of prisons and managing prison queues. Recourse to such mechanical and short-term measures actually signals a need for more permanent changes in penal policy (dealing with high re-offending rates) as well as for a shift in people’s attitudes. One way of achieving this is to find viable alternatives to imprisonment. However, most societies have yet to discover how to punish their offenders such that the punishment would satisfy the demands of various social groups and simultaneously reform the offender’s ways. Existing sentencing options such as compulsory participation in social and treatment programmes, community work, fines, and reconciliation orders all represent alternatives to imprisonment yet fail to meet these two criteria fully. Moreover, scepticism and too little information about alternative sentences have made it difficult to rally public support for alternative ways of treating offenders *5 . Lowering the number of inmates remains an unpopular policy that governments cannot easily explain to the electorate.

The other option for achieving a reduction of imprisonment rates is to change the attitudes held by the public. Some researchers believe that offender-adverse public opinion is actually capable of leading to the imposition of tough sanctions *6 , while others hold punitive publics to be a reflection of public penal policy *7 . Regardless of the mechanism actually at work, the European Social Survey (2010) *8 points to the Estonian population as being relatively punitively oriented. When people were asked which sentence they would impose on a 25‑year‑old house burglar, 64% of Estonians were in favour of imprisonment, making Estonia ninth from the top on the list of the countries favouring imprisonment (the average preference rate was 60%). The lowest preference for imprisonment was expressed in Finland (42%) and the highest in Ireland (73%). Irrespective of the criticism levelled against more public involvement in sentencing, recent years have witnessed appeals to increase it from the academic domain and seen a spate of corresponding policy initiatives – e.g., the introduction of lay assessors in courts *9 . The growing involvement of the public in punishment decisions makes studying penal attitudes and the factors that influence them a more valuable task that holds potential for considerable practical application. Besides other results, such studies are likely to highlight the legitimacy level of the sentencing practices really employed –discrepancies between the sentences actually imposed and people’s understanding of proper punishment would suggest that practitioners of jurisprudence and policy-makers need to improve the communication and explanation of their decisions. Estonia has witnessed a number of ‘pushmi-pullyu’ approaches from politicians whose penal policy is at best described as inconsistent and who appear to lack information about what their constituents actually desire. The declared goal for their penal policy may be to reduce the number of prisoners, yet the decisions they make pave the way to construction of new mass-incarceration institutions and they preach condemnation and shaming as the purpose of sentencing.

This article analyses how public penal attitudes, and indirectly penal policy, can be shaped by social and political trust and the public’s perceptions about the aims of punishment. A trust in the society and its institutions could reflect belief in the competency expressed in the institutions’ choices, while trust in strangers could serve as an indicator of belief in the rights of people to be equal members of society *10 and in people being capable of change *11 . This could, furthermore, influence the way people perceive offenders (either as outcasts or as fellow members of society) and the choice as to their treatment (to impose either isolation or, on the contrary, more rehabilitative treatment) *12 . There are several studies that have examined the relationship between penal attitudes and various types of trust *13 . Similarly, research has explored the links between the aims behind punishment and punitive attitudes *14 . In this paper, we propose a single model to connect all these factors.

2. The theory

2.1. Aims behind punishment

The most commonplace way of classifying the aims for punishment is by grouping them under the headings ‘preventive (utilitarian)’ and ‘retributive (non-utilitarian)’. The point of punishment according to utilitarians is to diminish future offending; utilitarians believe also that punishment should be proportionate to the gravity of the crime. For them, punishment is, above all, a functional response. In contrast, non-utilitarians aim at achieving justice – for them, reforming the offender is of secondary importance. According to non-utilitarians, each offence deserves a reaction. While utilitarians look to the future, non-utilitarians are focused on the past and seek to bring about fairness *15 .

Another way of understanding the aims for punishment is to distinguish between shaming and educative punishments. Shaming-oriented punishments as emotional responses to the acts of an offender are triggered by talionic eye-for-an-eye attitudes *16 . Such responses are derived from either sympathy for the victim or anger at the offender *17 . The principal idea with an educative punishment is to bring the offender and the victim together in order for the offender to better understand the consequences of his or her act. Shaming punishments are monologues by the state, while educative punishments promote dialogue, with the aim of repentance *18 .

Preference for a particular aim of punishment has to do with what people consider to be the causes of crime, which, in turn, is at least partially related to their worldview. Those who think that crime is a matter of personal choice favour justice-related punishment aims, while those who recognise that the causes of crime may have their roots in the offender’s social setting are likely to prefer other goals. An earlier study showed that students who subscribed to labelling theory and structural positivism as explanations of crime tended to take a less punitive stance *19 . In other words, those who believe that crime can be explained by societal inequalities rather than by personal choice would opt for milder approaches in the treatment of offenders *20 .

Earlier studies have found also that those for whom the aim of sentencing is to incarcerate the offender are more punitive in their attitudes *21 . Similarly, people who are more vengeful tend to support retribution and incapacitation as punishment’s aims *22 .

Clarity about the aims for sentencing is one of the core aspects of deciding on the sentence itself. R.S. Frase *23 argues that vague intuitions related to the objectives behind punishment tend to give way to personal beliefs, which in situations wherein the decision is up to a single judge creates a risk of fragmentation of sentencing practices. An insufficiently clear understanding of the purpose for punishment is likely to distort the results, while a good sense of that purpose and of the type of punishment best suited to the case should reduce the subjective element in sentencing.

2.2. Trust

In the social-sciences literature, a distinction is commonly made between two types of social trust, generalised and specific *24 . This article looks predominantly at generalised trust, a measure of confidence that obtains among strangers. The complementary concept – specific trust – refers to trust among family members and friends. Generalised trust is a notion that better reflects people’s confidence in anonymous members of society, offenders among them.

Generalised trust (trust in strangers) expresses people’s perceptions about society *25 . Perceived group threat is one explanation for harsh, highly punitive attitudes – the dominant group protects its position, demonising the less fortunate by manipulating public opinion accordingly *26 . Antipathy towards ‘the other’ and making the less fortunate into scapegoats are predictors of harsher, more punitive feelings *27 . For the public, harsher punishments are a way of controlling a threatening group. It has been shown also that anger about and fear of crime evoke punitive feelings *28 . When news media encourage personal identification with the victims of crime, they thereby stoke anger against criminals, and tabloid-media consumption as the main source for one’s news appears to add to fears of crime and amplify punitive attitudes *29 . People who are angry about crime are also people who feel less secure, and they therefore are likely to transform their anxiety into harsher punitive feelings *30 . People who are trusting, on the other hand, tend to be more tolerant of fellow members of society *31 . Trusting people believe in reforming the offender. They are prepared to share a certain degree of responsibility for the offender’s acts and wish to avoid the suffering that would be caused by harsh punishment, for they see the offender as potentially valuable to their society *32 . In high-trust societies, the message of punishment to the offender includes an invitation to co-operate *33 . Moreover, high-trust societies are less concerned about crime *34 .

According to researchers, political trust, measured as confidence in the various political institutions (political parties, the government, the police force, etc.), is a strong predictor of social trust, which suggests that to a certain extent social trust is a product of political trust *35 – a conclusion contested by other authors *36 . In comparison to social trust, political trust is impersonal and mediated. This means that the origins of social trust lie in personal connections, while political trust is shaped by news media and other mediated sources. Political trust is related to one’s belief in open government, and its measure depends on how well the political system works *37 . People who do not trust politicians tend to be unhappy with the outcomes of their policies, including those intended to counter the perceived threat of crime. When people feel that crime is a problem they are more likely not to trust the government *38 and to believe that the government’s response to the crime problem is inadequate. Crime salience and crime-specific concerns (e.g., worries about drug trafficking) have been found to predict punitiveness in attitudes at the level of the individual *39 . It has been argued that a decline in political trust is, in fact, behind the rise in imprisonment rates in the US *40 .

3. Data and methods

The data used in our analysis were obtained from a poll commissioned by the Estonian Ministry of Justice and conducted by Turu-uuringute AS in Estonia in January 2014 through a regular omnibus survey. The method used was simple completion of a questionnaire via face-to-face interviews, and the response rate was 27%. The sample consisted of 500 respondents over 15 years of age who were representative of the Estonian general population: The sample consisted of 42% men and 58% women, with 53% representing the 15–49 age band and 47% being 50 or older. As for education level, 16% had had an elementary or primary education, 58% had a secondary or vocational education, and 26% had received at least some higher education.

3.1. The variables

3.1.1. Length of sentences / severity of punishment

In many studies, punitiveness is measured as a complex index composed via multiple statements (that there should be a universal increase in the severity of sentences, that offenders should be harshly punished, etc.), for which respondents are invited to express their degree of support *41 . Another technique that is sometimes used involves having respondents choose between individual sentencing options, such as imprisonment vs. community service. This method is used by, amongst others, those administering the European Victimisation Survey *42 . Our study, following the example of Swiss researchers *43 , uses length of imprisonment as the measure of the severity of punishment. In addition to supporting simplicity, this technique aids in overcoming the complexity problem – i.e., the issue of the particular meaning that respondents attribute to certain types of punishment. The length of imprisonment as a measurement continuum is more apt to describe what people consider a severe punishment compared to choosing between different types of punishment. For example, although it is widely assumed that imprisonment is the harshest form of punishment (since it includes severe limitations on personal freedoms), researchers do not know which of the options presented is actually considered more/most severe by a particular respondent. After all, the myth of Sisyphus has it, the toughest punishment of all consists in being compelled to do work that serves no purpose.

The questionnaire consisted of four vignettes, each containing a description of an offence and background information about the offender. The types of offences in these vignettes were domestic violence, embezzlement from a bank, violent robbery of a shop, and burglary by a repeat offender. For each scenario, the respondent was invited to answer a series of questions, about the type of sentence that would, in his or her view, be appropriate in the case at hand and – in the question that elicited the data for this paper – the length of the prison sentence that he or she would impose (as a number of days/weeks/months/years) in a situation in which imprisonment is the only option (without suspension of any portion of the sentence). Described in brief, the domestic-violence scenario involved a married couple whose quarrel, caused by jealousy, led to violent conflict, with the female needing medical help because of bruises and aching ribs. The embezzlement case involved a clerk who embezzled 360,000 euros in the course of five years. In the vignette presenting violent robbery of a shop, the robber threatened a saleswoman with a knife and made off with, in total, 2,200 euros. Finally, the burglary scenario involved intrusion to the cellars of a block of flats and causing 6,500 euros in damage. All of the perpetrators except the burglar, who was a repeat criminal, were first-time offenders. Also, apart from the bank employee, all the offenders were either drug or alcohol addicts. Some additional background details on the offenders were provided to the respondents, such as age, childhood circumstances, education, and/or employment status.

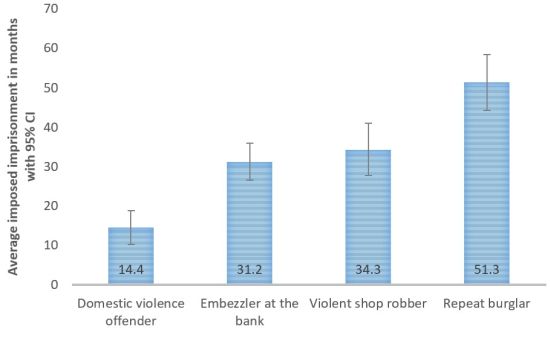

Of the four scenarios, the one attracting the most severe sanctions was that of the repeat burglar: the average imprisonment the respondents chose to impose here was 51.3 months (4.2 years). The shortest prison term was imposed for the domestic-violence offender (14.4 months, or 1.2 years). One of the reasons the burglar tended to be assigned the most severe punishment might be his prior convictions (according to the case write-up, he had already had eight convictions), while the other scenarios involved first-time offences.

Figure 1. Average length of imprisonment imposed (in months)

For every scenario, the distribution of the prison sentence imposed was positively skewed. For primarily this reason, we decided to forgo analysis of average sentence lengths and to focus our further analysis on the most extreme sentences. In the first step, we separated the respondents who preferred harsh sentences from those who favoured milder ones: considering the length of the sentences, for each offence we classified the responses in the band of approximately 10% that represented opting for the longest terms of imprisonment as extremely punitive. In the case of the domestic-violence offender, the preferred term of imprisonment within this decile was 36 months or longer (accounting for 9.5% of the respondents); for the cases of embezzling and violent robbery, it was 60 months or longer (a sentence assigned by 15.8% and 16.5% of the respondents, respectively); and for the repeat burglar, it was 120 months or more (10.9% of the respondents). In total, 37% of respondents selected an extremely long sentence (i.e., one in the top decile) in at least one of the cases.

As the next step, we compiled a new composite index, according to which those who did not belong to the extremely punitive group for any of the offences were denoted with ‘0’, while those whose response qualified as extremely punitive in one case received the indicator ‘1’ and those who represented the top decile in two or more cases were designated as group 2. Respondents who gave no answer for at least one of the questions were omitted from the analyses. The distribution of the extreme sentences by percentage and absolute number is shown in Table 1.

Choosing only extreme answers better reflects opinions of those people who are consistently more punitive-minded in more than just one scenario. Those who were less punitive in their attitudes, as reflected in not choosing such a value for more than one scenario, were used as a comparison category. This facilitated analysis by enabling us to describe punitively minded persons relative to the rest.

Table 1: The proportion of extreme sentences

| Frequency | Percentage |

0 | 313 | 62.5 |

1 | 108 | 21.7 |

2 (≥ extreme choices) | 67 | 13.4 |

Total | 488 | 97.6 |

Data missing | 12 | 2.4 |

3.1.2. Aims behind the sentencing

The respondents were given a list of general aims pursued via sentencing (not related to the scenarios above) and instructed to evaluate the importance of each on a four-point scale (with ‘1’ meaning ‘not important at all’ and 4 meaning ‘very important’).

Punishing the offender and reacting to the offence were seen as the most important aim (considered ‘very important’ and ‘important’ by 96% of respondents) together with compensating the victim (also 96%), while reconciliation between the parties to the offence was regarded as the least important (69%). In principle, respondents saw aims that are quite different and even contradictory as equally important – a finding that is consistent with the results of earlier studies *44 . The results from our study are supported by previous studies also in that respondents elsewhere too appear to prefer punishment of the particular offender responsible and the prevention of further offences over rehabilitation of the offender *45 . The modest support displayed for the goals of restorative justice, reconciliation among them, might be due to a lack of information about the principles and impact of restorative justice.

Figure 2. For various aims behind sentencing, the percentage of respondents who considered each aim either important or very important.

To understand whether certain aims of sentencing could be considered in combination, we performed a principal component analysis. This analysis showed that there were three aims that were strongly correlated with each other as compared to the rest: to isolate the offender and protect society, to serve as a warning to others, and to express society’s condemnation of the act (see Table 2, below). This component clearly distinguishes a group of people for whom societally oriented aims of punishment are important. Societal aims revolve around the protection of society, while the others (i.e., individual- and victim-related goals) have to do with targeting the particular offender, along with his or her behaviour, or the victim. Because of their justice-seeking aspect, societal aims are linked mainly with non-utilitarian punishments. For making the best use of the information about correlations between distinct items under ‘aims of sentencing’ and to prevent multicollinearity effects, the component ‘societal aims of sentencing’ yielded by the principal component analysis was utilised in further analysis.

Table 2: Results from principal component analysis (the component explains 53% of the original variables)

| Component loadings | Communalities |

To isolate the offender and protect society | 0.78 | 0.42 |

To serve as a warning to others | 0.76 | 0.61 |

To express society’s condemnation of the act | 0.65 | 0.57 |

3.1.3. Social (generalised) trust

On a four-point Likert scale, where ‘1’ represented ‘very trustworthy’ and ‘4’ ‘untrustworthy’, 62% of the respondents considered most people in Estonia to be very trustworthy or somewhat trustworthy (‘1’ or ‘2’, respectively), while 34% considered them either not very trustworthy or untrustworthy. The 4% who did not respond were excluded from further analysis.

3.1.4. Political trust

In the opinion polls and questionnaires used in studies that investigate ‘political trust’, this term may refer to confidence in political parties, the government, the parliament, or politicians *46 . Trust in parties and in politicians appear to reflect very similar attitudes. According to the European Social Survey 2012 *47 , the level of trust in political parties was almost identical to that in politicians in Estonia – politicians were considered untrustworthy by 14.8% of respondents and political parties by 14.6%, while 0.6% of respondents indicated that they completely trust politicians and 0.4% expressed the same attitude vis-à-vis political parties. Trust in the parliament was slightly higher, the corresponding figures being 11.6% and 1.4%. Political trust in our study means belief in politicians and was measured by means of the 4-point Likert scale, where ‘1’ signified ‘complete belief that the Estonian politicians are doing their best for the country’ and ‘4’ denoted total disbelief in that proposition. According to the results, 33% expressed ‘complete belief...’ or tended to believe in (trust) politicians, while 60% tended not to believe in them or had no belief (trust) in them. Seven per cent did not respond and hence were excluded from further analysis.

3.2. The results

To analyse the various factors contributing to the selection of an extreme sentence, we used multinomial logistic regression models (see Table 3). The choice of logistic regression over a linear model was based on data-related requirements: a linear model would not have been optimal in light of the data’s skewness with respect to the lengths of sentences. The dependent variable was the number of extreme sentences on the scale 0 to 2. We composed models to compare the likelihood of a respondent meting out one extreme sentence to that of him or her not choosing any extreme punishments and to compare the chances of handing out two or more extreme sentences to those of giving none. The independent variables were the aims for sentencing, political trust, and social trust. In addition, we used socio-demographic control variables: age, gender, ethnicity (Estonian vs. non-Estonian, as 2/3 of the Estonian population are Estonians while most of the rest are Russian, followed by smaller groups of Ukrainians and others), and education.

Table 3: Odds ratios from the logistic regression model for extreme sentences (reference category: no extreme sentences)

| 1 extreme sentence | 2 or more extreme sentences |

Aim behind sentencing: protection of society | 0.98 | 2.00** |

Social trust: belief that people are very or somewhat trustworthy | 0.44** | 0.43** |

Political trust: full belief or tendency to believethat politicians are doing their best for the country | 0.52* | 0.47* |

Gender: male | 1.36 | 2.26* |

Ethnicity: non-Estonian | 1.42 | 1.06 |

Education1 : primary or less | 0.86 | 0.19** |

Education: secondary | 1.12 | 0.78 |

Education: vocational | 0.87 | 0.50 |

Age | 1.00 | 1.03** |

Constant | -0.37 | -2.29 |

N | 436 |

|

Nagelkerke R² | 0.192 |

|

Model chi-squared | 76.2*** |

|

* p<0.05; **p<0.01

1 The reference category for level of education is at least some higher education.

We discovered that high social and high political trust both reduce the risk of imposing extreme sentences on offenders. In other words, trusting individuals are milder towards offenders. Looking at the aims of punishment, one can see that those who prefer emphasis on broad societal aims tend to be more punitive. However, the effect was statistically significant only in the case of two or more extreme sentences; i.e., it mattered only when respondents were systematically punitive and selected an extremely long imprisonment term in two or more cases. In the case of systematic punitiveness, the findings support earlier research suggesting that men are more punitive *48 . Surprisingly, in a contrast to findings from some earlier studies *49 , people with lower education levels appeared to be somewhat less punitive in our study. This could be explained by social affiliation – people belonging to the same social class are likely to experience group solidarity, and, since offenders usually have a modest education, those with lower educational qualifications would tend to be more tolerant towards offenders. It is appropriate to point out in this connection that, of the four vignettes presented in the questionnaire, three involved ‘ordinary’ (less-educated) criminals. A study conducted earlier in Estonia lends support to the solidarity hypothesis, under which people with a lower income would be expected to prefer community-service sentences over imprisonment *50 . Another finding was that age had a positive effect on the severity of punishment – older people preferred harsher sentences, a finding consistent with those of some earlier research *51 . Ethnicity did not have an effect on the dependent variable.

4. Discussion and conclusions

The study demonstrates that social and political trust are good predictors with respect to punitive attitudes. People who do not trust strangers and are sceptical of politicians would impose longer sentences on offenders. The relationship between trust and punitiveness applies for incidental as well as systematic punitiveness – whether or not the respondent chose an extremely severe sentence for only one of the offenders (expressing incidental punitiveness) or imposed a harsh sentence on two or more offenders (expressing systematic punitiveness), the degree of trust that he or she had in strangers or in politicians would still largely determine the level of punitiveness. In addition, our study shows that one’s notions of the aims behind punishment are a strong predictor with regard to systematically severe, highly punitive approaches. Those for whom the central aim with punishment is the protection of society are more punitive. That is, people for whom the main aims for sentencing involve isolating the offender, condemning him or her, and deterring other would-be offenders are more punitive than those who do not consider these aims to be of central importance.

The relative mildness of the sentences handed out by those who trust strangers is explained by their greater tolerance of and belief in other members of society. Trusting individuals are less apprehensive about outgroups and are, therefore, likely to be less punitive. Also, people who have faith in other members of society believe themselves not to be deliberately denied access to societal resources and hence do not see a need to defend themselves against ‘others’. This stands in contrast to the concerns of those who feel that society (which they define narrowly, excluding those groups perceived as ‘other’) needs protection and who consequently express more punitiveness. Trusting people are more open towards others, while those who lack trust would rather exclude groups who are perceived as inherently different.

The less punitive attitudes of those who have trust in politicians are explained by their confidence in the government’s actions in the fight against crime. The variable expresses people’s belief that politicians act in the best interests of their country. Individuals who are trusting are less suspicious of government policy and its real-world ability to curb crime, and they are, accordingly, not prone to experience intense emotions with regard to crime. This makes them less punitive.

Thus, a narrow understanding of the aims behind punishment paves the way to experiencing pronounced punitive feelings. In other words, punishment being seen as for condemnation, waving a warning finger at would-be criminals, and isolation (that is, it being seen as applied to protect society) results in harsher, more punitive attitudes. Isolation makes further offences against members of society impossible; i.e., the longer the imprisonment, the more long-lasting the protection. Condemnationexpresses the public’s disapproval of the act of committing the offence; this reflects strong punitiveness and an eye-for-an-eye approach. Disapproval is an emotional assessment that feeds in to the vicious circle of punitiveness, since emotions have been shown to trigger harsher punitive feelings. Warning other potential offenders is a moralistic wagging of the finger at would-be criminals that is likely to have little effect (the effectiveness of general deterrence depends on various factors, such as the likelihood of getting caught, the target group’s eventual addictions, and mental condition) *52 .

The findings presented above suggest several important conclusions. In an environment of high social and political trust, it is easier to reduce the public’s punitiveness. Consequently it will be easier to find support for policies aimed at more individualised and therefore less harsh penal laws as opposed to ‘one-size fits all’ punishments where minimum punishment levels outweigh individual characteristics and needs of offenders. The latter can be achieved without controversy only when the corresponding measures are supported by public opinion – i.e., in a climate of enlightened penal attitudes. Any long-term reduction in the number of prisoners must come through a deliberate policy choice; it is unlikely to be achieved as an incidental side effect of crime‑reduction.

On the practical side, besides measures directly targeted at reducing prisoner numbers, the focus of incarceration-rate reduction programmes should be on shifting the opinions of systematically punitive social groups, whose views about the aims behind punishment may warp public opinion and, in so doing, have a negative impact on the fulfilment of those programmes’ aims. Swiss researchers *53 demonstrated that it is not the general public who hold abnormally punitive attitudes but, rather, a certain part of the population. Only a small percentage of the population (in the case of the study reported upon here, about 13% of the respondents) are systematically punitive, yet their voices often drown out milder and more reasonable opinions, thereby giving politicians an incentive to shoot down policies that would bring imprisonment rates down. Educating this group through explaining the aims of punishment and their relationship to various types of sentences is a way of overcoming systematic punitiveness, and it appears to be a good start for shaping a social environment that is conducive to introducing individualised penalties and reducing the number of prisoners. Other important ways of preparing the ground for a downward shift in incarceration rates include fostering social ties between people and enacting policies that support and intensify social involvement – all measures strengthening social trust *54 .

pp.32-42