Crime, Culture and Social Control

25/2017

ISBN 978-9985-870-39-6

Issue

Explaining the Relationship between Social Trust and Value Similarity: The Case of Estonia

The article is dedicated to explaining why value similarity fosters generalised social trust in high-trust societies. Previous findings by Beilmann and Lilleoja suggest that value similarity is more important in generating individual-level social trust in countries where the overall levels of social trust are higher, while in countries with a low level of social trust, congruity of the personal value structure with the country-level value structure tends to be coupled with lower trustfulness on the part of individuals. The article explores the meso-level indicators that could explain this relationship. The relationship between social trust and human values was examined in a sample of 2,051 people in Estonia, using data from the European Social Survey, round 7. The results suggest that when differences in socio-economic factors are controlled for, value similarity remains a significant factor in fostering generalised social trust in Estonian society. However, its direct effect is relatively low when compared with predictors such as trust in certain institutions, economic well-being, and ethnicity. Trust in the legal system and the police plays a particularly important role in fostering generalised social trust in a high-trust society wherein people believe that other people in general treat them honestly and kindly.

Keywords:

social trust; European Social Survey; value similarity; human values

1. Introduction

Generalised social trust has been proven to be extremely beneficial both at country and at community level: it is related to many positive outcomes, among them good governance and an effective state *1 , *2 , *3 , economic growth and good economic performance *4 , *5 , *6 , crime reduction *7 , *8 , and greater overall happiness and well-being *9 , *10 . These predominantly positive societal outcomes of generalised social trust result from one important quality of trust – it facilitates co‑operation between people and among groups of people. Many social theorists have considered trust an important building block of society precisely because society could not function without co-operation. N. Luhmann *11 , for example, is one of those authors who emphasises the importance of trust as a facilitator of co-operation and a major contributor to the maintenance of social order at the micro level.

Generalised social trust can be defined as the willingness to trust others, even total strangers, without the expectation that they will immediately reciprocate that trust or favour *12 , *13 , or a belief that others will not deliberately cheat or harm us as long as they can avoid doing so *14 . Therefore, generalised social trust is foremost a social norm that we learn from our environment: some people become trusting because they experience trustworthy behaviour in their day-to-day life, whereas others, because they live in communities where it is not reasonable to trust others, learn not to trust other people *15 , *16 , *17 . Indeed, it would even be stupid to trust generalised others in places where the levels of generalised social trust are low, since anyone who tries to co-operate in a society lacking social trust will simply be exploited *18 . Therefore, it seems that the existence of community- or country-level generalised social trust is a prerequisite for individual-level generalised social trust.

When one considers the extremely positive outcomes from generalised social trust, a question logically follows: why is there more generalised social trust in some societies than in others? Modernisation *19 , democracy *20 , an accordant high level of political rights and civil liberties, social and economic equality *21 , *22 , *23 , *24 , *25 , *26 , a strong universalistic welfare state *27 , *28 , a trustworthy state and good governance *29 , *30 , *31 , *32 , *33 , low corruption in the legal system *34 , *35 , *36 , ethnic homogeneity *37 , *38 , a Protestant tradition *39 , *40 , *41 , individualistic values *42 , *43 , *44 , *45 , *46 , and value similarity *47 , *48 , *49 have all been found to be important factors for generating high levels of social trust at country and community level. However, one should not overlook the individual‑level differences in levels of generalised social trust within societies, because groups within a given society may differ substantially from each other. Therefore, it is important to consider micro-level predictors of generalised social trust as well, and there is evidence that at the individual level of generalised social trust is influenced by a wide range of socio-economic and contextual factors: income, education, age, and many others *50 , *51 , *52 , *53 .

In this article, we explore the relationship between social trust and value similarity further. There is growing evidence that value similarity may foster generalised social trust in society *54 , *55 . Similarly to M. Siegrist and colleagues *56 , K. Newton *57 claims that it is easier to trust other people in homogenous societies wherein people know that others share largely similar interests and values. Furthermore, individuals benefit from holding values similar to those of their reference groups because people are likely to experience a sense of well-being when they emphasise the values that prevail in their environment *58 .

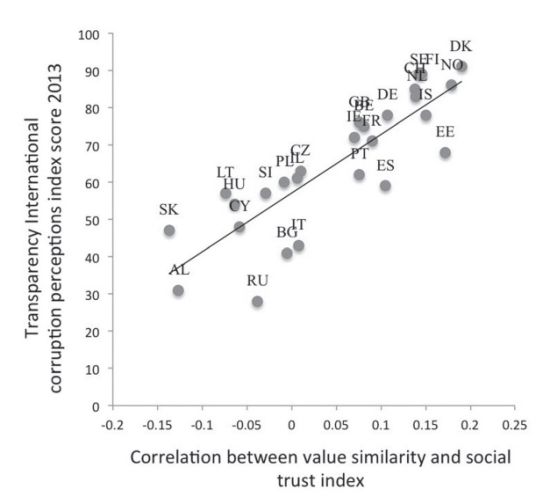

Because the theorising and some previous findings suggest that people find it easier to trust total strangers if holding the same values as the prevailing values in the relevant society or community, M. Beilmann and L. Lilleoja *59 tested whether value similarity indeed fosters generalised social trust in society. There was found to be a stronger positive relationship between value similarity and generalised social trust in countries that have high generalised social trust levels, while in countries with very low levels of generalised social trust the congruity of personal value structure with the country-level value structure tends to be coupled with individuals’ lower trustfulness. As generalised social trust is inversely related to perceived corruption *60 , it is not surprising that there is also a strong country-level relationship between, on one hand, corruption perceptions levels and, on the other, the amount of correlation between generalised social trust and value similarity (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Correlation of generalised social trust and value similarity across countries, plotted against the overall perception of corruption.

Value similarity is more important in generating individual-level generalised social trust in countries where the overall levels of generalised social trust are higher and perceived amounts of corruption are lower. With this article, we aim to test which meso-level indicators could explain this relationship in Estonia, which belongs to the group of countries wherein generalised social trust is high. To this end, we analyse for which groups in Estonian society value similarity is more important in creation of generalised social trust.

2. Method

2.1. The data

European Social Survey data from round 7 that were collected in Estonia in 2014 were used for this research. The European Social Survey, or ESS *61 , is an academically driven social survey to map long-term attitudinal and behavioural changes in more than 20 European countries. The ESS provides comparable data for nationally representative samples collected to the highest methodological standards across countries. Answers on generalised social trust and human values were available from 2,051 respondents in Estonia, with females accounting for 59% of participants. Around 63% of the respondents were Estonian-speakers and 37% Russian-speakers. On average, the respondents were 50.3 years old (SD = 19.08) and had completed 13.2 years of full-time education (SD = 3.38). Hence, the survey was representative of all persons aged 16 and over (with no upper age limit) residing in private households. The sample was selected by strict random probability methods at every stage, and respondents were interviewed face-to-face.

Our Social Trust Index was composed of three indicators:

(1) Trust: ‘Would you say that most people can be trusted, or that you can’t be too careful in dealing with people?’ (0 = ‘You can’t be too careful’ … 10 = ‘Most people can be trusted’)

(2) Honesty: ‘Do you think that most people would try to take advantage of you if they got the chance, or would they try to be fair?’ (0 = ‘Most people would try to take advantage of me’ … 10 = ‘Most people would try to be fair’)

(3) Helpfulness: ‘Would you say that most of the time people try to be helpful, or that they are mostly looking out for themselves?’ (0 = ‘People mostly look out for themselves’ … 10 = ‘People mostly try to be helpful’)

The index computed was based on the average of the standardised scores for these items. The overall standardised alpha of the three-item measure was 0.74, with an average inter-item correlation of 0.589.

2.2. Measurement of value similarity

Our conceptualisation and measurement of value similarity relies on S.H. Schwartz’s *62 conceptualisation of human values. Schwartz has defined values as desirable, trans-situational goals, varying in importance in serving as guiding principles in people’s lives. According to his original theory, each individual value in any culture is locatable with respect to 10 universal, motivationally distinct basic values – hedonism, stimulation, self-direction, security, universalism, benevolence, conformity, tradition, power, and achievement–which, on the basis of their interrelationships, form a universal circular structure. Similar value types are close to each other, and conflicting values appear on opposite sides of the circle. Pursuing one type of value always results in conflict with types of values opposite it *63 .

Human values can be measured by means of Schwartz’s portrait value questionnaire (PVQ‑21), which consists of 21 indicators. To assess the similarity of individuals’ value preferences with the central value profile of Estonian society, an individual-level value similarity measure was created in line with the procedure of Beilmann and Lilleoja *64 . For each individual, rank order values for all 21 value indicators were estimated, and correlations with the value hierarchy were then determined, on the basis of the average scores for the Estonian population. The Spearman correlation coefficient for each calculation was used as a value similarity measure for each respondent.

2.3. Other variables

Our Index of Trust in Institutions was computed as a composite score based on the two indicators ‘trust in police’ and ‘trust in the legal system’ (0 = ‘Do not trust the institution at all’ … 10 = ‘Completely trust the institution’). Feelings about income were measured on a four-point scale (1 = ‘Living comfortably on present income’; 2 = ‘Coping on present income’; 3 = ‘Living with difficulty on present income’; 4 = ‘Living with great difficulty on present income’).

3. Results

Table 1 presents standardised regression coefficients from multiple regression analyses, with generalised social trust as the dependent variable and trust in institutions, the language spoken in the home, the overall feeling about the income, age, gender, individual-level value similarity, and years of education as independent variables.

Table 1: Standardised regression coefficients (dependent variable: generalised social trust)

Trust in institutions | 0.32*** |

Home language (1 = EST; 2 = RUS) | -0.12*** |

Feeling about the income | -0.12*** |

Age | 0.08*** |

Gender (1 = male; 2 = female) | 0.06** |

Value similarity | 0.06* |

Years of education | 0.05* |

Adjusted R2 | 0.18 |

*** p < .001, ** p < .01, * p < .05

All of the factors tested have a significant relationship with generalised social trust. In line with expectations, the strongest predictor for generalised social trust was the level of confidence held by an individual in the legal institutions (the police and the legal system). In an Estonian context, generalised social trust differs with ethnic group – the Estonian-speaking majority tend to be more trusting than the Russian-speaking minority. People who feel economically secure report higher levels of generalised social trust than do people who are finding it difficult to cope with the present income. The effect of age on generalised social trust is positive; that is, older residents tend to be more trusting. The same is true of women and highly educated respondents. When all of the named variables are included in the model, there exists also a significant effect of value similarity, which means that, irrespective of their socio-economic background, Estonian residents whose value schemes are more similar to the country‑level value structure are more trusting.

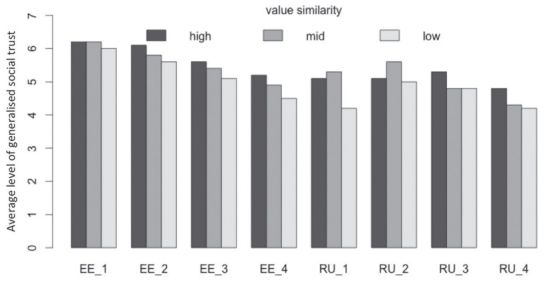

To depict the effect of value similarity on trustfulness in more detail, the next image (Figure 2) illustrates levels of generalised social trust across the main differentiators – ethnicity and economic coping – while comparing individuals on the basis of the congruity of their personal value structure with the Estonian general value structure.

Figure 2. Generalised social trust in relation to ethnicity, feelings about income, and value similarity *65 , where EE = ‘Estonian-speakers’, RU = ‘Russian-speakers’, 1 = ‘Living comfortably on present income’, 2 = ‘Coping on present income’, 3 = ‘Living with difficulty on present income’, and 4 = ‘Living with great difficulty on present income’.

Among Estonian-speakers, the trends are very clear – throughout each economic group, the respondents with greater value similarity are, on average, more trusting than those with less value congruity. At the same time, better economic coping is systematically associated with a higher level of generalised social trust.

In general, the Russian-speakers tend to be less trusting than Estonian-speakers, and for them economic welfare and generalised social trust do not show a linear relationship. In terms of economic coping, the most trusting Russian-speakers are those who ‘cope’ on the present income, whereas individuals who are living comfortably on the present income show a level of generalised social trust similar to that of those who find it difficult to cope with the present income. In a similarity to the ethnic majority, the least trusting are those Russian-speakers for whom coping with the present income is very difficult.

As for value similarity, the least trusting Russian-speakers are the ones with low value congruity and the economically least successful respondents. High value congruity corresponds to a higher level of generalised trust among poorly coping Russian-speakers, but an equivalent relationship is not so clear among economically more successful ones.

4. Discussion and conclusions

It has been claimed that people tend to trust those who are more like them and who share similar values *66 , *67 . Recent results indicate that this is indeed true in high-trust societies but not in countries where overall generalised social trust is low *68 . With this article, we aimed to go further toward explaining the relationship between value similarity and generalised social trust on meso level, using Estonia as an example.

Our results suggest that when one controls for differences in socio-economic factors, value similarity remains a significant factor fostering generalised social trust in Estonian society. However, its direct effect is relatively low in comparison with predictors such as trust in the institutions considered, economic well-being, and ethnicity. When we analysed value similarity in the context of these last two variables, some substantive differentiation appeared. There exists a very clear positive relationship between value similarity and generalised social trust among the Estonian-speaking majority but not among the Russian-speaking minority. On one hand, this could be explained by the cultural differences, but when one considers economic circumstances too, these results seem to mirror the problems related to social cohesion. Social and economic equality have been found to be important factors for generating social trust *69 , *70 , *71 , *72 , *73 , *74 , and it seems that the economic problems facing the Russian-speaking minority in Estonia affect their trust in other people more strongly than such problems influence their Estonian-speaking counterparts. If we take into account that generalised social trust is strongly related to trust in state institutions, it seems plausible that the Russian-speaking minority’s distrust in state institutions leaves them less trusting of people in general. In that connection, we have to consider differences in culture and in the resulting expectations that the ethnic majority and minority have for state institutions. P. Ehin and L. Talving *75 have demonstrated that Estonian- and Russian-speaking people in Estonia have rather different expectations with regard to the functioning of democracy in the country. Estonian-speakers’ expectations are related mainly to aspects of procedural justice, while Russian-speakers see social justice much more often as a crucial part of well-functioning democracy. Because expectations of the state taking care of the social and economic welfare of its citizens are an important issue for many members of the Russian-speaking minority, there may result lower rates of trust in state institutions that have fallen short of their hopes for more social and economic justice, and low trust in these institutions could, in turn, result in lower levels of generalised social trust.

In consideration of the most important predictor of generalised social trust, the relationship between generalised social trust and institutional trust is not surprising, because a trustworthy state and good governance *76 , *77 , *78 , *79 , *80 and, secondly, low corruption in the legal system *81 , *82 , *83 are found to be important factors for creating high levels of generalised social trust at country and community level. B. Rothstein *84 has advanced the idea that trustworthy state institutions – especially non-political state institutions such as the legal system and police force – play the key role in generating generalised social trust because, when people see that the officials with state institutions treat people equally and are not involved in corruption, a highly visible example is offered that it is reasonable to expect honesty and trustworthiness even from people whom one does not know very well. Corrupt state institutions, on the other hand, are often considered one of the main causes for low levels of generalised social trust, because people learn from these that they can trust people only very selectively *85 , *86 . Therefore, trustworthy state institutions seem to play the key role in building high-trust societies in which people share the values that lead them to treat other people honestly and kindly in general, regardless of whether they belong to the same social groups as those people.

pp.14-21