32/2023

Issue

Protection of the Right to Privacy in States’ Unilateral Access to Extraterritorially Located Data in Criminal Investigations

The process of striving to enhance law enforcement's access to digital data held extraterritorially while finding the right balance in fundamental-rights protection began with establishing the Convention on Cybercrime. Evolving risks of evidence being lost, intimately connected with the urgency of collecting digital data, impose a constant need for new, more efficient models for data acquisition and access. The article examines the set of mechanisms connected with states gaining access unilaterally (without needing foreign states’ assistance) to extraterritorially located data from the perspective of protecting suspects' privacy and family-life rights. In light of the fact that one virtually steps onto foreign ground to gain such access, most states have refrained from regulating it domestically and have officially addressed the issue by means of international co-operation instruments created for situations significantly different from this, yet investigators in circumstances such as a domestic criminal investigation wherein the only connection to the other state lies in an e-mail message sent via a foreign service provider ought to avoid resorting to extremely burdensome mutual legal-assistance instruments. At the same time, sufficient domestic guarantees of fundamental-rights protection should be in place.

The author proposes a model for unilaterally accessing extraterritorial data that considers the rights of individuals involved in criminal procedure and, alongside these, state interests in unilaterally accessing and receiving extraterritorially held data.

Keywords:

fundamental rights; right to private life; extraterritorial data access; criminal investigation

Introduction

As of January 2023, there were more than five billion Internet users, accounting for 64.4% of the globe’s population. Of this total, 4.76 billion, or 59.4% of the world's population, engaged in social-media use. *2 The recent unprecedented speed of growth in digital technology and the convergence of computing and communication devices have together come to dictate how we socialise and do business – and how crimes are committed. Today, it is impossible to imagine a world without the Internet.

The endeavour to enhance law enforcement's access to digital data held extraterritorially in a manner that strikes the right balance in fundamental rights’ protection is a process that started with establishment of the Budapest Convention on Cybercrime. The latest efforts are the Second Additional Protocol to the Convention on Cybercrime, for enhanced co-operation and disclosure of electronic evidence *3 , and continuing discussion of the European Union ‘e-evidence proposal’ *4 . The urgency of collecting digital data is always connected to the risk of evidence being lost, hence the constant need for more efficient data acquisition and new access models. However, bumping up against territoriality, matters of virtual territoriality specifically, has created issues that challenge traditional thinking.

Consensus seems to have been reached that traditional mutual legal assistance (MLA) is ineffective in cases of requesting volatile digital information *5 . States have therefore turned to informal co-operation mechanisms and started asking for data directly from service providers. Since these providers respond on a voluntary basis and in line with their own conditions, thereby producing a fragmented landscape and unpredictable, perhaps unsatisfactory outcomes for law enforcement, international co-operation instruments designed to render mutual help more effective, such as the European Investigation Order (hereinafter ‘EIO’), have been introduced. Nonetheless, several countries have responded to these developments by beginning to explore another question: under what conditions may authorities request access to data by applying their domestic tools and thus circumvent burdensome international co‑operation mechanisms. In the case United States v. Microsoft Corp., the US court system had to consider the circumstances in which law-enforcement agents in the United States may obtain digital information from abroad. The Microsoft Ireland dispute in question ended at Supreme Court level. On 30 March 2018, the US Department of Justice moved to drop the lawsuit, with Microsoft filing its agreement with that motion. The Supreme Court then dropped the case. At that point, the government and Microsoft maintained that the newly passed CLOUD Act had rendered the lawsuit meaningless in that the law had created clear new procedures for obtaining legal orders for data in cross-border situations of the relevant nature.

After the US legislature passed the CLOUD Act into law and the European Commission began discussing the e-evidence proposal, a new instrument arose in their wake: state-to-ISP co-operation. This mechanism is meant to enhance the effectiveness of accessing digital data held outside the requesting state. Even though states recognise that obtaining data from foreign servers is a breach of sovereignty *6 , there are ongoing efforts to establish more efficient structures for mutual legal co‑operation, with new forms of co-operation being formulated accordingly, states still seek legal opportunities to access extraterritorial data unilaterally. This phenomenon is especially prominent in ‘dark Web’ *7 investigations; since it is possible to claim a ‘loss of location’ *8 here, the foreign-territory issue never arises. However, if matters of international law such as sovereignty are left aside and one addresses this issue from the perspective of a suspect, the question of protection of fundamental rights, especially the right to protection of one’s private life, arises.

This article focuses on examining states' unilateral access (i.e., access not depending on help from a foreign state) to extraterritorially located data via the lens of protecting suspects' right to their private and family life. The discussion here examines whether there is any significant difference in the protection and guarantees of suspects' rights if a state unilaterally accesses and copies data material that resides outside its physical territory as opposed to requesting it from the other state. The question is situated within the context of recent trends toward international collaboration in digital collection of information. This paper positions it alongside analysis of protection of suspects' right to a private life.

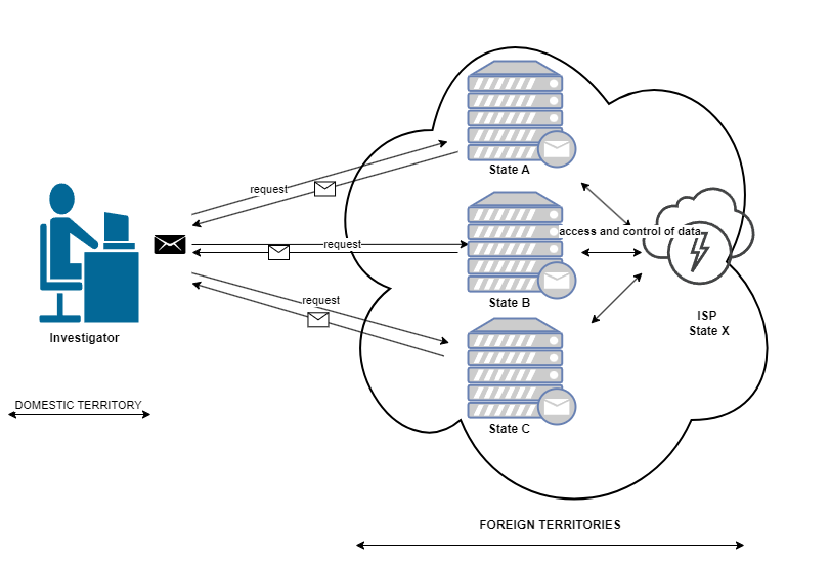

The figure above illustrates the situation of unilateral extraterritorial access to data held in different jurisdictions. The https request sent by the investigator takes less than a second, and the response (marked with an envelope symbol) consumes just as little time. This is the connection to foreign territories. Tackling the attendant issues in terms of granting sufficient guarantees for fundamental-rights protection allows us to argue that unilateral access to data is not entirely a question of intra-state regulations and entails certain international obligations. Still, those obligations must not influence adherence to protecting the fundamental rights of subjects in criminal-law procedure. For the analysis below, traditional legal methods such as analytical comparison are applied.

I present a model for unilaterally accessing extraterritorial data in cases of so-called domestic investigations wherein the data are accessible and there is no need to request help of any kind. This approach permits me to argue that there may be identifiable cases in which the connection to the other state is so insignificant that it would be safe to assume there to be no interest of the other state in assessing the virtual actions taken on its territory (namely, performed on the server located there). The proposed model considers suspects' rights in criminal proceedings and other states' interests in unilaterally accessing and receiving extraterritorial data. Therefore, all those cases wherein there is an obvious significant interest of the other state lie beyond the scope of this article. *9 Neither does the paper discuss issues that, in theory, could arise from the fact that the other state might, by principle, not be co-operative in criminal‑procedure settings even if the investigation is of a domestic nature and the only connection to the investigating state lies in the location of the ISP. These questions are not addressed in the article since their answers do not affect the fundamental-rights guarantees extended to suspects and, therefore, deserve an approach different from that taken here.

I posit that there should be robust domestic legislative strides motivated by pursuit of the strictest protection for fundamental rights in connection with the grounds for those extraterritorial measures taken by states in their domestic criminal investigations that might have a connection to another state. Domestic legislation for unilateral extraterritorial-data access should be grounded in judicial review and should, by default, consider the interests of the foreign state.

Suspects’ right to a private life

Unilateral access to stored computer data is tightly bound up with the right to respect for one’s private and family life. Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights *10 (hereinafter ‘the ECHR’) encompasses the right to respect for these, along with one’s home and correspondence, with protection for the confidentiality of private communications, whatever the content of the correspondence might be and whatever form it may take. According to the Court's case law, telephone calls are covered by the notions of ‘private life’ and ‘correspondence’ for the purposes of Article 8’s Section 1 *11 , and it similarly addresses e-mail *12 , instant-messaging messages *13 , and information that is derived from the monitoring of personal Internet usage *14 and from other data stored on computer servers *15 or hard drives. *16 This means that the confidentiality of all the exchanges individuals may engage in through their communication is protected. There is no de minimis principle for deeming interference to have occurred: opening a single message is enough. *17 Article 8 covers all forms of interception, monitoring, and seizure, all of which could come into play in states' unilateral access to extraterritorial data.

That unilateral access to extraterritorial data is described in Article 32 b of the Convention on Cybercrime. Article 32 represents an attempt to regulate trans-border access to digital data, defined as accessing or receiving stored computer data held within another state-party territory through a computer system in the investigating state’s territory. Article 32 refrains from defining access as search (and seizure). To access and receive data in such a manner, the latter state would need to have the genuine consent of the person with lawful authority to disclose the data to the requesting party through the relevant system. In contrast, Article 19 of the Convention on Cybercrime regulates the search and seizure of stored computer data located on the investigating state's territory, thus articulating a difference between accessing and copying, on one hand, and searching and seizing (thereby making unavailable), on the other.

Legal scholars have argued that with computer searches the one-step search process is replaced by a two-step search process wherein the first step is to seize the digital data medium and the second is to search for the digital data on that data medium. *18 Indeed, search for digital data is very different when there is a possibility of searching for the data while one is in possession of the data medium as opposed to when there is no physical access to that medium. The latter precludes a chance of recovering data that the user has locally deleted. *19 For instance, the extent to which an investigator going through the contents of an e-mail account can copy material is limited to the data accessible to the end user. Therefore, content such as user-deleted files is out of the reach to the investigator. On the other hand, when seizing a data medium on which e-mail messages are managed in a raw or ‘meta’ form (e.g., a server), the investigator can look for a much richer set of data, including data deleted from the user’s perspective. States' unilateral access to data does not afford the possibility of seizing the actual data medium; hence, the investigatory authorities gain access to fewer data.

In a broad sense, it is possible to distinguish between two types of situation involving unilateral access to potentially extraterritorially located data *20 – namely,

1) situations wherein the data become accessible during a public investigative measure (e.g., in the course of a search) and

2) situations in which the data are accessible during surveillance measures.

Both of these measures are conducted on the physical territory of the state authorising said actions under its legislation. During an authorised (home) search, the opportunity of accessing a functional device might arise and, with it, an opportunity to access various ‘cloud-computing’ (external‑server-based) accounts connected to the suspect *21 . The same kind of access to data is obtained via surveillance measures of various sorts. Because the data accessible thereby reside in foreign territory, international co-operation instruments are used – the external server is traditionally considered foreign territory. However, in establishing whether there is an infringement of rights related to a person’s private life or correspondence, where precisely any individual datum resides or has resided is of no relevance. The ECHR protects the confidentiality of all forms of communication between natural persons, covering all communication that has taken place via the modern technologies that millions of people use for everyday interaction.

The conditions on which a state may interfere with the enjoyment of a protected right are set forth in paragraph 2 of Article 8 of the ECHR. Namely, this is permitted in the interests of national security, public safety, or the economic well-being of the country; for the prevention of disorder or crime; for protection of public health or morals; or in aims of protecting the rights and freedoms of others. Limits to the rights are allowed if ‘in accordance with the law’ or ‘prescribed by law’ and at the same time ‘necessary in a democratic society’ for honouring one of the above-mentioned objectives. The language ‘in accordance with the law’ implies that domestic law must provide a mechanism of legal protection against public authorities’ arbitrary interferences with the rights safeguarded by virtue of Article 8, Section 1 of the ECHR. In this respect, the national law must be clear, foreseeable, and adequately accessible.A signatory state has a positive obligation, inherent to Articles 3 and 8 of the convention, to enact criminal-law provisions effectively and apply them in its practice through effective investigation and prosecution.

To be deemed of an appropriate extent, domestic fundamental-rights protection has to meet certain criteria. Firstly, the prevailing level of attention to protecting suspects’ private life and the secrecy of correspondence attests that it is strict. In the absence of a de minimis principle, all forms of communication fall under Article 8 of the ECHR because any form of interception, monitoring, seizing, accessing, copying, etc. applied must be explicitly permitted by law. In connection with this, data categorisation too is of importance – ‘content data’ (the payload) traditionally enjoy the highest level of protection, relative to, for example, traffic details, or ‘traffic data’ (a form of metadata). Consequently, it is noteworthy that the lowest possible threshold was set in the Court of Justice of the European Union judgement in Case C‑746/18 *22 , which responded to a preliminary-ruling request from the Estonian Supreme Court with regard to processing of personal data in the electronic‑communications sector. It was decided that any permission even for location and traffic data alone, notwithstanding the fact that a judge need not grant the request for such data, has to be given by an independent body (and not by the police or a prosecutor either, for that matter). This leads to the conclusion that all other categories of data need more extensive protection, since it is possible to derive information on the habits of one’s day-to-day life, permanent or temporary places of residence, daily or other movements, the activities carried out, the social relationships of at least the persons concerned, and the social environments frequented by those individuals by means of said data.

To ensure compliance with the above-mentioned conditions, the access granted to the competent national authorities for retained data must be subject to prior review either by a court or by an independent administrative body and to the condition that the decision of that court or other entity be made in light of a well-reasoned request by those authorities submitted in line with, among other things, the framework of procedures in place for prevention of, detection of, or prosecution for crime. *23 With the decision described above, the Court of Justice of the European Union ruled that even traffic data deserve independent oversight and that access to this material shall not be taken lightly. It is clear that access to other, ‘higher’ categories of data has to be controlled more strictly and subjected to more protective measures. A broad interpretation of the right to one’s private life leaves no possibility of assuming that some forms of communication would be excluded. In summary, the domestic approach to protecting private-life and communication rights has to be strict if it is to meet the standards for fundamental-rights guarantees.

At this juncture, it bears reiterating that states' unilateral access involves data stored in various remote Web-based accounts and that, accordingly, the matter of infringement of fundamental rights comes into question. Traditionally, to receive such (extraterritorial) data, states would need to appeal to mutual international co-operation instruments, because voluntary international co-operation thus far has not extended to stored content data as it has to traffic data. The reason for this divergence seemingly has lain in the more serious breach of data subjects' fundamental rights that accessing the former may constitute. Nevertheless, states have started taking a separate tack, through regulations that distinguish between receiving/accessing digital data and doing the same with data in physical form, where the latter has traditionally been subject to mutual international co-operation.

Mutual international co-operation and data collection

Mutual legal assistance is the formal method by which states request and aid in obtaining evidence located in one state to assist in criminal investigations or proceedings in another state. This instrument functions for receipt of electronic content data from foreign service providers. In contrast, non-content data in many cases may be requested directly from foreign service providers in settings of voluntary co-operation. The notions of sovereignty and trust guide governance of MLA. Since the assistance requests typically must comply with the laws of both the requesting and the request-receiving state, the individuals targeted benefit from the protection afforded by both legal systems.

In Europe, the Convention on Mutual Assistance in Criminal Matters addresses MLA between EU countries *24 . However, when considering the context of e-evidence, states have continuously sought solutions that can improve speed and effectiveness while simultaneously protecting the fundamental rights of participants in criminal proceedings. Therefore, another instrument was introduced: the European Investigation Order (EIO) *25 for criminal-law matters *26 . The fundamental principle behind the EIO is mutual recognition and trust. This means that the executing authority is, in theory at least, obliged to recognise the request of the other country and ensure execution, while the issuing authority should ascertain whether the evidence sought is necessary and proportionate for the proceedings; whether the investigative measure chosen is necessary and proportionate for the gathering of the evidence in question; and whether, by means of issuing the EIO, another Member State should be involved in the collection of that evidence.

Full respect should be accorded to fundamental rights in the course of issuing and executing an EIO, and this duty indeed is explicitly recognised in the corresponding directive’s first article (in para 4 *27 ). It also establishes limited grounds for refusal of execution, in Article 11. Notwithstanding these grounds for refusal, the option of resorting to them has rarely been exercised *28 ; the very low number of refusals (cases of non-execution) reflects the implied trust in the other party's legal system. The European Union’s advocate general has stated, in a request for a preliminary ruling, that ‘the role of the issuer is to be the guarantor of legality and, by extension, individual rights, and therefore, it has to complete the form most appropriately to ensure that the executing authority which receives it is in no doubt that the conditions laid down in Article 6(1) of Directive 2014/41 have been respected’ *29 . *30 The division of roles is clearly established – the issuing state carries the burden of ensuring proportionality, legality, and respect for the fundamental rights in need of protection.

The Court of Justice of the European Union has concluded that in the event that the national law of the issuer does not comply with the ECHR's minimum standards, said Member State shall not issue EIOs *31 . Advocate General Michal Bobek has expressed the opinion that *32

whoever wishes to use the system of judicial assistance and mutual recognition under Directive 2014/41, or under any other instrument of judicial cooperation and mutual recognition for that matter, must come, metaphorically speaking, with clean hands, or [,] rather, cannot come with hands that are knowingly dirty. The failure to observe that rule of basic hygiene, which has been repeatedly recognised and systematically emphasised, may indeed lead to that person being asked to leave the room and to come back only after having found some soap and carried out the necessary procedures.

The report on Eurojust's casework in the field of the EIO focuses on issues identified in cases handled by that agency’s national desks over the span of a two-year reference period starting on the deadline date for transposition (22 May 2017). During that reference period, Eurojust registered 1,529 cases involving EIOs in its case-management system. According to the report, only a few cases featured non-execution issues. Eurojust has not dealt with cases wherein fundamental-rights grounds were at stake. *33 The numbers listed are not surprising, in that one of the aims for EIOs was to create a smoothly functioning comprehensive instrument for obtaining evidence in cases with a cross-border dimension on the basis of the principle of mutual recognition and trust. *34 One should bear in mind, though, that the requests often are for ‘physical’ investigative measures on foreign soil – interviewing a witness or searching a house, circumstances demonstrably requiring help from another state – measures that could not be conducted unilaterally. Therefore, the EIO represents an effective and low-bureaucratic-hurdle instrument of state-to-state co-operation, one that EU countries have welcomed. The very low number of related disputes in the courts and the overall satisfaction evident from Eurojust's statistics lead to the conclusion that there are no prominent issues with trusting each other's legal system.

Furthermore, not only is the state-to-state co-operation in the EIO domain simple and trustful, an additional possibility is foreseen for a state's unilateral conduct on another state's territory: interception of telecommunications without a need for technical assistance. In the relevant cases, a notification procedure still enables the target-territory state to object to said unilateral activities. Yet, if there were a recording device in a car travelling across Europe from one state to another that records everything taking place in that car and (should it have a door or window open) in its vicinity and if this recording were extracted in domestic jurisdiction, the activity would not necessitate any notification per the rules on EIOs.

It is not entirely clear why a conversation via telecommunication media is treated differently from face-to-face communication in a room or what the reason might be for granting less protection to conversations that are not conducted by means of telecommunications. Could this distinction be connected to the notion that data from or related to the latter are going to get stored while one would not expect data to be repeated by interception of telecommunications? Even if so, the reason for drawing a distinction between the two forms of data should be stated explicitly. Such inconsistencies tend to leave an impression that the issues connected with data and territoriality have not been thoroughly thought through.

Notification per the EIO Directive is designed to inform the other state about the unilateral investigative measure. The Member State so notified may, in circumstances wherein the action would not have been authorised in a corresponding domestic case, respond that said activity may not be carried out or shall be terminated, and it may notify the requester, where necessary, that any material already collected may not be used or is to be used only under the conditions that the responding state shall specify separately. Given that the cornerstone for the EIO directive is general rather than universal mutual trust and effectiveness of evidence collection, notification of such unilateral activity should not be deemed to constitute an order to recognise any investigative measure; it is a mere reflection of respect for the other country's sovereignty. This is an act of comity that should never bring about any challenges related to the legality of evidence collected through the investigative measure carried out by the Member State submitting the notification. The provision for this mechanism should be interpreted in light of the values of freedom, security, and justice, with mutual trust and respect for different legal systems serving as its basis. In practice, states indeed are answering requests smoothly and thoroughly, bearing in mind the above-mentioned values and the aim articulated for the instrument.

In summary, while one can characterise the notification requirement’s existence as implying that unilateral evidence collection on foreign soil is not an absolutely ‘silent’ procedure that other states have no interest in knowing about, resorting to grounds for objections against evidence collection is rare. Notification is carried out for comity reasons only, with the element of trust holding a crucial role.

Significantly, notification became a key element for the European-level efficiency-focused instrument that followed in this domain. At the heart of the discussions stemming from the adoption by the EU Council of Ministers of its ‘general approach’ to electronic evidence, on 7 December 2018, was the meaningful requirement to notify *35 . Since the EIO is widely believed to have still not brought the desired effectiveness for e-evidence requests and to make it easier and faster for law-enforcement and judicial authorities to obtain ‘e-evidence’, the Commission had, on 17 April 2018, proposed setting forth new rules in the form of a Regulation and a Directive instrument that create a European Production Order and European Preservation Order. *36 The proposal is aimed at improving legal certainty and expediting the securing and obtaining of electronic evidence stored and held by service providers established in another jurisdiction. The main feature of the system envisioned is allowing for requests to be submitted directly to private companies, irrespective of the data’s location or the storage mechanism and without involvement of foreign-state authorities in the first place. It would co-exist with the judicial co-operation instruments currently in place (such as the EIO and MLA). *37

It has not been possible to reach the quick agreement sought with regard to such new EU rules for law-enforcement authorities. However, in a press release on 29 November 2022, the Commission reported that the European Parliament and the Council had reached provisional political agreement on future EU legislation on obtaining e-evidence. At the crux of the negotiations overall was the question of the procedure for the notification. It was agreed that the authority in the originating Member State (the ‘issuing authority’) has to notify the authorities where the service provider is located only if the relevant individual does not reside in the issuing state or the offence was not committed there and only if traffic or content data are sought. Another important condition agreed upon is that the authority notified shall be allowed to invoke any of several grounds to refuse the order – e.g., by citing protection of fundamental rights or appealing to immunities and privileges. *38

The disputes arising from the e-evidence proposal indicate that states value a meaningful notification system. Whether they value a system with an integral challenge mechanism and whether one would be necessary is still being determined. Debates thus far have drawn considerable attention to the necessity of bringing the Member State of the affected person’s residence into the equation too. In contrast, Eurojust has echoed the majority’s opinion about notification pursuant to the EIO rules (where no assistance is needed), expressing the position that notification is purely for reasons of comity and shall not supply any grounds for questioning legality related to the evidence collected. According to the legal literature, in trans-border remote search-and-seizure situations, international law offers no basis for a specific obligation to notify the other state about a trans-border investigative measure even if the reason proposed for notification by states consists merely of comity considerations. Nevertheless, ‘the gesture of notification’ may be beneficial for diplomatic relations between countries. *39

Expected criteria for unilateral access to extraterritorially located data

The expanding use of Internet-based services, in tandem with which cybercrime is increasing, puts strong pressure on states in connection with their responsibility to protect society and individuals alike against crime, by means that include effective criminal investigations and prosecutions. All instruments employed to this end assume that the state has appropriate safeguards in place for protecting human rights and fundamental freedoms. In practice, this assumption has seldom been challenged: use of the EIO has not yielded any disputes rooted principally in that issue. States' unilateral access to extraterritorial data for purposes of copying must, by default, mesh with the potential interests of other states, since there still is access to foreign ground, even if measured only in milliseconds. The developments in international co-operation suggest that states do have significantly less interest in investigations that are ‘purely’ domestic. Nonetheless, it has to be guaranteed that the domestic actions would, in principle, be agreeable to the other state also from the standpoint of protecting the fundamental rights of a party to a criminal proceeding.

The first and most important prerequisite for unilateral access to extraterritorial data consists of a domestic legal regime that strongly values the protection of human rights and fundamental freedoms. All mutual co-operation instruments rely on trust in this. Domestic legislation’s interpretation of the ‘private life’ notion must be broad, then, with all forms of communication falling under this umbrella and all being protected accordingly. Stored messages are considered content data that deserve the fullest protection, so judicial authorisation is generally needed for ensuring the necessary level of protection. States must acknowledge a broad interpretation of communications and the necessity of judicial review if they are to meet the commensurate standard of fundamental-rights protection.

The requirement for strong domestic guarantees of fundamental rights’ protection creates a need to regulate computer-system searches explicitly. Hence, one must ask how to word a regulation granting permission to take investigative measures on foreign soil without the data‑subject's consent. The wording used in Article 32 b of the Convention on Cybercrime, ‘accessing and receiving’, discriminates between seizing (which makes something inaccessible) and searching. *40 In essence, accessing and receiving involves a request message sent to a server located extraterritorially, after which the data are copied. Having lawfully gained access to said data, an IT-ignorant investigator might not even consider the fact that this sequence of events includes milliseconds of virtually stepping onto foreign soil, and such an investigator is bound to continue acting in accordance with the domestic regulation alone, honouring the rights of the suspect according to domestic rules. Therefore, states that have left computer-system searches or accessing computer data through another computer system unregulated may face strong criticism for lack of clarity as to which rules apply if an investigator has access to an e-mail account for purposes of copying content data. In circumstances where no legal regime for this is established, ascertaining the answer in any given case seems to be left to the best judgement of an investigator. Hence, the data might not enjoy any of the protection that judicial review would extend.

An additional criterion should be applied for computer-system searches: ‘serious crime’. Extraterritorially held data ought not be legally accessible unless the investigation pertains to a serious crime. The e‑evidence proposal sets the same criteria for producing transactional data and producing content data. In contrast, orders to produce subscriber and access data may be issued in relation to any criminal offence, with the justification that ‘this threshold has been chosen to ensure a balance for all Member States between efficiency of criminal investigations and protection of rights and proportionality’. *41 This threshold has the further advantage of being easily enforceable in practice.

With adequate safeguards established in the domestic legal system, the aspects that follow may be tackled properly by way of international responsibilities. That said, not all states are willing to declare that they have no interest in foreign states' actions on their territory. This fact is vividly evident in ongoing discussions’ fierce disputes about notification in relation to the e‑evidence proposal. Those discussions revolve around fundamental rights and protecting the right to a fair trial; still, these interests are connected mainly to the states’ citizens and to a fear that data under the control of an ISP located in the target territory could get used in a manner that said state regards as unacceptable. In these circumstances, domestic legislation would compass different rules for immunities and privileges, which may refer to particular categories of people (such as diplomats) or specifically protected relationships (such as those falling under lawyer–client privilege or the right of journalists not to disclose their sources of information) or other citizenships. In a situation wherein, the criminal procedure is purely a domestic one, other states probably have very little interest in being part of the data-collection process, even if the data at issue are controlled by an ISP within their territory.

To some extent, the principles outlined above have already been enshrined in practice. For instance, in dark Web investigations, states have stopped considering the option of disputing possible sovereignty factors (if they ever raised the issue at all). Such investigations are generally welcomed rather than feared by other governments *42 . Here, the servers are situated somewhere physical, just as in non-dark-Web cases, yet the focus of these investigations is rarely on identifying where the servers are such that the state in question can be notified. Instead, and quite obviously, the intent is to identify the individuals who are hiding their identity. Only after the suspects have been unmasked are the necessary avenues of co-operation sought. The application of this approach supports concluding that states are more interested in protecting the fundamental rights of their citizens than they are in being notified about every virtual step on their ground.

Conclusions

In nearly every criminal investigation, some evidence exists in or takes on digital form. That has led states to seek possibilities for better co‑operation and test their legal systems so as to determine suitable admissibility rules for domestic court proceedings. Therefore, this article’s analysis of the suspect’s right to a private life and the guarantees that a state should offer for the protection thereof during criminal proceedings that involve unilaterally accessing extraterritorial digital data is especially pertinent.

It is important that the confidentiality of all exchanges individuals engage in for communication is currently protected, with no de minimis principle applied for permissibility of interference. Additionally, all forms of interception, monitoring, and seizure, any of which could be subject to states' unilateral access to extraterritorial data, are subject to protection as lying within spheres of private life per practice under the ECHR. Because unilateral access to extraterritorial data is obtained for receiving and copying data for investigation purposes, there is a significant difference from seizure or rendering inaccessible. Notwithstanding the received data being only accessed, received, and copied, the infringement of fundamental rights, especially that of a person's right to a private life, is significant. For example, a Gmail user might employ a ‘timeline’ feature that could give investigators valuable information about times, dates, and locations; e-mail exchange (which could go back several years), and messages begun but never sent (stored in a drafts ‘folder’). Additionally, there might be smartwatch information linked to the account. In many cases, multiple people could be using a single account, not all of them suspects. With unilateral data access, the breach of private life is considerable, especially since companies that offer online services usually encourage people to apply and inter-connect those services to the fullest extent possible.

Investigative measures for accessing, receiving, and copying user‑accessible *43 content data are often unregulated in the domestic legislative arena in many respects because the data accessed may well reside on foreign ground, on a foreign server. The fact that one takes a virtual step onto that foreign ground, however brief, has been the decisive factor in refraining from regulating this domestically. The only way in which most states have officially addressed the issue is by using burdensome international co-operation instruments that were originally developed for situations significantly different from these. Moreover, the technical elements of the investigative measure considered here might be misunderstood by investigators, who often lack the necessary training. Should the international perspective be overlooked, situations may frequently arise wherein this investigative measure is treated as merely another (domestically regulated and convenient) investigative action. Therefore, practice might not honour the fundamental-rights guarantees required.

Nevertheless, treating access to extraterritorial data as a matter of international co‑operation would be the traditional and correct path. Current court practice and legislative steps show that the intent in this situation is to simplify the procedures and delineate the set of cases wherein the investigation is not domestic but ‘really’ international. Suppose the only connection to the other state in a criminal investigation is an e-mail message sent by a foreign service provider. Investigation in that domestic case should not necessitate resorting to extremely burdensome mutual legal-assistance instruments. The guarantees domestically afforded for fundamental rights should suffice, as mutual trust between states in international co‑operation leaves the heavy burden of ensuring the proportionality and legality of the request to the issuing state. Therefore, a domestic legislature striving for the strictest, most robust protection of fundamental rights would provide the necessary foundation for such extraterritorial measures taken in states’ domestic criminal investigations as might have a connection to another state.

Strong domestic legislation addressing unilateral access to extraterritorial data should be built on pillars of judicial review and should, by default, consider the interests of the foreign state. Given the significant breach of private-life rights involved, permission for any such measures should be justified through the lens of the ultima ratio principle. Domestic legislation should set minimum-threshold requirements for a data request that are rooted in the mutual international co-operation criteria. Most importantly, unilateral access to extraterritorial data should be allowed in investigation of a serious crime and where either parties to criminal proceedings have a substantial connection to the issuing state or a suspect is not identified yet. Should there be any apparent interest of the state on whose territory the ISP is located, the domestic judge should dismiss the request and mutual international co-operation instruments should be applied instead *44 . Because notification between states is essential here, domestic legislation should additionally foresee an obligation to notify the affected state for the sake of comity even in circumstances in which no apparent interest has been detected. Given the existing practice built on trust between states in aims of enhancing international co-operation in digital data‑sharing, domestic legislation that recognises the interests of other states is most likely to be welcomed.

In light of the resource requirements attendant to mutual international co‑operation, even with the ‘simplified’ instruments (such as EIOs), as things stand – without a clear regulative basis in domestic legislation – it remains too easy to turn a blind eye to the extraterritoriality factor and treat the act of accessing extraterritorial data as a purely domestic one. This might most commonly occur for reason of well-intentioned investigators’ limited knowledge of the digital world; however, it nevertheless poses a significant risk to the private life of data subjects who are parties in criminal proceedings. Therefore, domestic legislation should consider the international facet to the investigative measure. That said, the legislator should not turn the matter into an onerous one of international co‑operation either, especially when other states are likely to lack interest in it anyway. Without proper balance, the expected protection of the private life of a party in criminal proceedings might get overshadowed by arguments about the possibility of collecting all evidence located extraterritorially.

pp.119-130