Current Developments in Legal Interpretation

27/2018

ISBN 978-9985-870-41-9

Issue

Interpretation of Undefined Legal Concepts and Fulfilling of Legal Gaps, in Juri Lotman’s Semiotic Framework

The article examines whether the structure of meaning proposed in cultural semiotics by the Tartu–Moscow School of Semiotics is applicable for the interpretation of undefined legal concepts and to the filling of legal gaps. With the assistance of Lotman’s cultural semiotics, one is able to formulate the regularities that operate in legal interpretation in the same way as in culture. One of these is the binary structure of legal concepts and gaps. In interpreting norms and striving to overcome legal gaps, it is necessary to define the external reference (‘utterance’) and the self-reference (‘text’) in law. The article clarifies and examines these in the legal context and reiterates the value of bearing in mind throughout the process that interpretation always takes place in relation to this binary structure.

Keywords:

Interpretation; Tartu–Moscow School of Semiotics; undefined legal concept; legal gap

1. Introduction

Lines of relation between semiotics and law have been drawn from several perspectives for more than half a century now. These areas of research demonstrate definite overlap. For example, the problem of interpretation of law features in both realms. Whereas semiotics is interested in the question of how the norm gains a meaning and what the structure of a meaning is, the question from a legal point of view is how to achieve conditions wherein a meaning of a norm is as constant as possible between interpreters and over different periods of time. The aim for this article is to examine whether the structure of meaning proposed in cultural semiotics by the Tartu–Moscow School of Semiotics (TMS) is applicable for the interpretation of undefined legal concepts and to the fulfilling of legal gaps. To accomplish this end, one must

1) introduce the chosen semiotic basis;

2) legitimately conclude that the TMS ideas should be applied to interpretation of law; and

3) from examples of case law, ascertain whether the semiotic findings identified truly appear in legal practice.

This article focuses on the implementation of the TMS semiotic programme for undefined legal concepts and for legal gaps. Research on this specific question has not been carried out before.

2. The theoretical framework of the Tartu–Moscow School of Semiotics as an input to legal interpretation

Interpreting law is in its essence a semiotic process – i.e., a process in which meaning is created, a sign process. Although the word ‘semiotic’ is rarely used in description of legal interpretation, postmodern theory of law dissects the exchange of information between the legal system and its surrounding environment. *2 It is evident that the process of legal interpretation as a communication process is analysable through semiotic methods and models. According to legal semiotician S. Tiefenbrun, a better understanding of the elements of semiotics provides the legal practitioner with the key to the communication and discovery of meanings hidden under the weight of coded language and convention. *3

There are many, quite different approaches to the semiotics of law, and the field is quite fragmented. Taking this into account, one must decide which authors to follow. *4 It should be noted that, along with the works of legal semioticians, the contribution of general semiotics can be used in the analysis of legal processes. The author whose work is most directly considered in this article has been chosen from Estonia – namely, Juri Lotman (1922–1993), a central figure of the TMS. Lotman did not concentrate on problems of law or on the relationships between juridical models, although aspects of juridical processes are nonetheless cited as examples in some of the TMS’s publications. *5

The TMS of the 1960s to 1980s, which played a vital role in the larger European intellectual‑historical context, *6 proposed a research programme while also positing certain principles of the functioning of culture and cultural phenomena. It should be noted at this juncture that the presentation of the TMS in this paper is not a historical endeavour, for not only do contemporary semioticians utilise the TMS contributions *7 but the semiotics school of Tartu is a ‘living’ entity, developing the approach of cultural semiotics further. While the core ideas were formulated in the 20th century, they have not lost their central position in Tartu’s semiotics and remain of value today.

Forming the beginnings of a brief introduction, the central concepts of the TMS, among them text, utterance, and primary and secondary modelling system, should be introduced. *8 Culture in its totality of meanings and processes was long a central topic of academic enquiry among TMS scholars. *9 For Lotman, the operational basis of culture is the text. Lotman wrote that the text itself, ‘being semiotically heterogeneous, interferes with the codes decoding it and has deforming effect on them. This results in shift and accumulation of meanings in the process of transferring the text from the sender to the receiver.’ *10

In defining culture as a kind of secondary language, scholars subscribing to the TMS introduced the concept of the culture text, a text in this secondary language. *11 Hence, the TMS concept of cultural semiotics implies that a semiotics of text (in particular, a semiotics of artistic text) is an indispensable constituent part. *12 For the Tartu–Moscow semioticians, secondary modelling systems became the fundamental object of study. *13 Particularly in later years, Lotman’s secondary modelling system method did not, however, get in the way of his message. *14 Nevertheless, it is important, and discussion of the question of secondary modelling systems continues in contemporary semiotics. *15

Lotman’s first definition of a secondary system came in the article ‘The Issue of Meaning in Secondary Modelling Systems’ (1965), later republished as a chapter in The Structure of the Artistic Text. A secondary modelling system is described there as ‘a structure based on a natural language. Later the system takes on an additional secondary structure[,] which may be ideological, ethical, artistic, etc. Meanings in this secondary system can be formed according to the means inherent to natural languages or through means employed in other semiotic systems’. *16

In a seminal collective work on the semiotics of culture first published in 1973, Theses on the Semiotic Study of Cultures (hereinafter, ‘Theses’), Lotman et al.state that

[a]s a system of systems based in the final analysis on a natural language (this is implied in the term ‘secondary modelling systems’, which are contrasted with the ‘primary system’, that is to say, the natural language), culture may be regarded as a hierarchy of semiotic systems correlated in pairs, the correlation between them being to a considerable extent realized through correlation with the system of natural language. *17

In Theses, the problem of one text existing at the same time in both modelling systems was pointed out: so long as some natural language is a part of language of culture, there exists the question of the relationship between the text in the natural language and the verbal text of culture. *18 The authors of the TMS solved the problem via distinguishing among three distinct relationships that are possible between text and culture:

a) text in the natural language is not a text of a given culture;

b) the text in given secondary language is simultaneously a text in the natural language;

c) the verbal text of a culture is not a text in the given natural language. *19

This leads to another important distinction with regard to texts and non-texts. The latter are called utterances. *20 Not every linguistic utterance is a text from the point of view of culture, and controversly, not every text from the point of view of culture is a correct utterance in natural language. *21 Lotman claims that for a culture text the initial point is the moment in time when the act of linguistic expression is not sufficient for transformation from utterance into text. *22 According to Lotman, what makes a text (as distinct from an utterance) is a certain order. For an example of this relationship, TMS scholars point to a poem by Pushkin that is at the same time a text in Russian. *23

3. Application to law

At the very first glance, it may seem that these semiotic statements about cultural phenomena have less to do with law. According to Lotman, however, practically all meaningful elements – from the vocabulary of natural language to the most complex artistic texts – act according to the same regularities. *24 As Continental European law is mainly a textual phenomenon, the interpretation of legal terms, when examined from the standpoint of sign process, follows the same regularities as other cultural phenomena. This is a fascinating point of view and is worthy of elaboration in the context of legal interpretation.

Tiefenbrun points out that, irrespective of all efforts at achieving objectivity in legal language through general use of referential terms, there is no doubt that the language of law is a distinct sub‑language, a special case of ordinary language that can and often does baffle non‑lawyers. *25 In other words, Tiefenbrun makes it explicit that legal language is secondary to natural language in a way similar to that in which the TMS sees artistic text as secondary to natural language.

A juridical text is without doubt a part of culture – it belongs to the legal tradition, and it is a part of the legal system in states, carrying the symbols and the ideology of those states. For illustration, one can point out that Continental law has a Roman-law background and contains many Latin concepts, such as culpa in contrahendo, in dubio pro reo, de iure, de facto, and ius commune.Latin terms are used frequently in German-speaking countries, and the transition in Estonian legal terminology from the Soviet era to the time of EU membership found one of its manifestations in the Estonian scholars’ usage of Latin terms in juridical journals. *26 It is evident that the law, given as a written text – most importantly in the Constitution and in acts of law issued by Parliament – constitutes both language and cultural text at the same time. This makes the question of primary and secondary modelling in a piece of law relevant in its own right. In the case of legal texts, the text in the given secondary language is simultaneously a text in the natural language (see item b above). Additionally, their relationship determines more than the meaning of the Latin terms when used in a contemporary social context. This can be expressed in another way too: the circulation between natural language as primary modelling system and legal language as secondary modelling system encompasses not only the words that seem alienbut all terms used in a law’s text. In the following subsections of the paper, this binary structure is presented as a translative process in law and as a structural principle of legal concepts.

3.1. Drafting and interpreting of legal concepts as two,

opposite semiotic processes

First of all, the very distinction between legal and natural language in a legal text attests to a legislative process being a translative activity at its core. What distinguishes a piece of law as a text rather than an utterance is a certain order that characterises law. Every legal text is a formalised text (with complicated language that is aimed at precision and with division into specific parts such as chapters, sections and subsections, paragraphs, and points and sub‑points) that possesses a margin of truth, which a non-text does not. *27 As referred to above, at the level of a primary modelling system legal terms are part of natural language, utterances, while at the level of a secondary modelling system they are part of culture text, more precisely juridical culture text. Therefore, in the legislative process, in the drafting or composing of a law, the words of the natural language (utterances – for example, ‘post box’) are transformed into legal language (in the same example, into the text ‘post box’ as defined in accordance with the Postal Act *28 ’s §8 (1) as ‘a facility for the delivery of postal items which is in the possession of the addressee’). The words of the natural language gain specific meaning that they did not have outside the culture text.

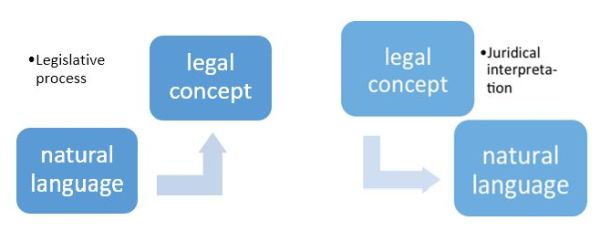

With another process, interpretation of a law, one sees a counter-process that entails the operation of transforming the legal concept back into the concept from natural language. This can be presented graphically as follows: *29

Figure 1. The legislative process (the concept from natural language becoming part of a legal text)

and the process of interpretation of legal concepts (finding of a meaning in natural language).

We can find another parallel with Lotman’s ideas in relation to our question of what constitutes good legal language. Namely, Lotman identifies how the moment at which a text turns back into its meaning in natural language corresponds to the moment wherein culture begins to crumble. *30 In parallel, if a legal text loses all of its specific terms and is completely open to free interpretation, it loses its binding nature; it stops being a text in a culture and becomes a non-text, general language. Or, in a counter process, if there is an increase in textual meaning, there is also a decrease in the meaning at the level of general utterance. By means of cultural semiotics, it can be explained that there is a tendency for texts seeking to express utmost high become hardly understandable for the addressees. *31 We can put these two semiotic tendencies into words thus: it appears that the legislature has to find a way to make the legal text as easily translatable into utterances as possible while retaining utility of the law. This conclusion, drawn by analogy from cultural studies, is not new, however. Legal theory, although not using the term ‘transforming utterances into text’, touches on the question by referring to ‘the margin of discretion’, *32 which in the language of semiotics would be ‘the number of utterances in law’. To sum up, we can state that Lotman’s idea of two separate modelling systems helps us to discover that there is a hidden binary structure not solely in legal language in general but to each legal term too.

3.2. A semiotic model of the binary structure

of undefined legal concepts and legal gaps

3.2.1. Undefined legal concepts

The margin of discretion in law is granted through the use of undefined legal concepts. As has been noted above, legal concepts articulated in the legal language function with a dual role. They circulate between legal and natural language. Through this, legal terms are, on the one hand, parts of the legal system that surrounds them, but at the same time they refer to the factual circumstances and values of the society and cultural space. Every legal concept has a binary nature – it is part of the legal space and of the extra-legal space. As Thomas Vesting describes it, this duality manifests itself in a) legal reproducibility (restoring the legal system) and b) legal change as a dialogue within a legal system. He writes that the interpretation of law has to tackle two issues with particular attentiveness: consistency in terms of repeatability of decisions (self-reference) and consideration of the structure of each particular case (external reference). *33 To my mind, this structural functionality has its foundations on the double‑structured language: the self-reference of a particular legal concept refers to the meaning in the legal language, whereas the external reference of a particular concept refers to the meaning in the natural language. The binary structure is especially clearly evident in the domain of undefined legal concepts. *34

The idea of an undefined legal concept (also called a blank concept) has its origins in German legal theory from shortly after the Second World War and, according to some sources, is not universally recognised in the systems of Continental Europe. *35 An undefined legal concept is set in opposition to defined legal concepts. It needs to be interpreted. According to the case law of the Federal Constitutional Court (Bundesverfassungsgericht), the room for interpretation should be determined in line with the aims for the law and it should be possible to control the outcome of the interpretation carried out by courts. *36 A defined legal concept, in contrast, is one that has a legal definition provided by law; therefore, according to Haase and Keller, a defined legal concept leaves no room for interpretation. *37

For example, §8 (6) of the Postal Act states requirements as to the location of post boxes in a village:

In a village, according to the agreement between the owner of a post box and a universal postal service provider, the post box shall be located at a place which is at a reasonable distance from the residence or seat of the person and in a place which is accessible by means of transport throughout the

year. *38

‘Post box’ in this case is a defined legal concept as described above, because it is defined in §8 (1) of the Postal Act. All the other words in this extract, in contrast, are not defined by law. What can be understand as the content of ‘agreement’, ‘reasonable distance’, or ‘accessible by means of transport’ is, therefore, a task for the interpreter, the person who reads and applies the law – probably a judge. The undefined legal concepts that govern the application of law can be very broad, as in the cases of ‘public weal’, ‘public interest’, ‘road safety’, ‘danger’, ‘reliability’, and ‘the ability of the people’. *39

In the interest of legal certainty, it must be required of the legislator that each norm be formulated clearly and unambiguously. At the same time, when finding a balance between flexibility of the law and legal certainty, the legislator may leave a certain margin of discretion to the law in order to afford reacting fairly in a particular situation. If a legislator uses an undefined legal concept to apply an element of discretion, a margin of discretion is granted to the authorities. Undefined legal concepts are fully verifiable by the court. Their interpretation falls under court authority. *40 Therefore, the use of undefined legal concepts is, on the one hand, an intentional method of the legislator for granting the power of interpreting a law to judges while, on the other hand, it is an unavoidable attribute of language.

3.2.2. Gaps

The same kind of duality characterises legal gaps. Each law inevitably has gaps *41 , and therefore it has long been recognised that the courts have the authority to fill these gaps. For example, pursuant to the Swiss Civil Code’s Article 1 (2) there is a court duty to fulfill the gap in the way a legislator would have done if there is no common law. *42 This process, judicial development of law, is considered a continuation of interpretation, where the two are seen as interconnected and as part of a gradual operation. *43 In the strict sense, interpretation is finding the meanings of the words of a law; in the broad sense, every time the judicial process settles the detail of any matter in solving a particular case constitutes a development of law, one that also serves the methodology of interpretation. Interpretation and filling of legal gaps go hand in hand; therefore, the same criteria that play a role in interpretation – in particular, the regulatory objective and the objective teleological criteria – apply to the overcoming of legal gaps. *44 A gap always exists as part of a legal system (self-reference); it should be filled with new material driven from society in a way that promotes the stability of the legal system (external reference).

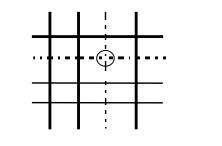

Claus-Wilhelm Canaris defines a legal gap by stating that a gap occurs when, in interpretation of possible meanings of the words of the law, there is no corresponding rule in the law even though the legal order as a whole requires one. In other words, a gap is an unplanned deficiency (Unvollständigkeit) of positive law. *45 The decisive question is whether the gap as a deficiency of valid law is obvious and, therefore, its elimination de lege lata by the applier (judge) is possible or, rather, it is a deficiency of the legal policy and legal system – i.e., a legal gap that must be removed by the legislator. This question must be answered on a case‑by‑case basis. *46 It is very important to emphasise that a gap in the law does not mean the presence of a ‘nothing’ but rather a “definite something”, which, according to the regulatory plan or the whole law, should form a certain rule. *47 When the gap is represented graphically, it can be seen as gaining its meaning from its context.

Figure 2. Legal gap as an absence of something certain.

From the moment of discovery of the legal gap, it is part of the legal text: semiotisation of the gap takes place. In decoding the gap as a semiotic phenomenon, we have the means to analyse it. Just as Lotman says when stating that the text can appear as a condensed programme of the entire culture, *48 we can conclude that every legal concept, and in the same way every legal gap, contains a model of the legal system. Filling a gap extends the law from its general idea to its lower levels because it requires an analysis of what is inherent in the legal order as a whole and what arrangement is most suitable for the legal system. In the process, the gap detected in the law renders the law more coherent with the society.

4. The binary nature of the undefined legal concepts

in relation to examples from case law

From comparison between defined and undefined legal concepts with regard to the tension between self-reference and external reference, it appears that in the case of defined legal concepts (as in ‘post box’ example) the balance in the tension between self-reference and external reference favours self-reference. This is so because defined concepts are autonomous and must always be interpreted in the same way within a given legal system. These elements of a system remain as they are and keep the stability of the system secure. In the case of undefined legal concepts, on the contrary (for instance, the reference to ‘reasonable distance’), there is more tension between self-reference and external reference: through undefined legal concepts, a significant amount of ‘foreign’ material ‘soaks in’, and this external material shapes the law as a whole. For that reason, one could conclude that the balance in the case of undefined legal concepts lies closer to external reference than self‑reference. Illustrative examples can be found in case law.

In consequence of European court and Estonian Supreme Court practice, interpretation of undefined legal concepts is not entirely free. Rather, it is based on the law in which the legal concept features. When looking into practice, the Constitutional Review Chamber of the Supreme Court of Estonia stated in 2005:

A blank concept is a legislative tool the legislator uses when it withdraws from issuing detailed instructions in the text of law and delegates the authority to specify a norm to those who implement the law. As blank concepts are created by the legislator, these have to be defined with the help of the guidelines and aims expressed by the legislator. *49

The Supreme Court has repeated the position expressed above – i.e., that the interpreter shall not be guided only by common usage or the usage of a term in other acts but must take into consideration also the wording and purpose of the act itself (in this particular case the Packaging Excise Duty Act). *50 In another judgement, a very recent one, the Administrative Chamber of the Supreme Court of Estonia stated that giving meaning to and interpreting a legal norm has to proceed from the entire legal system and use terms in their ordinary meanings, unless the provision in question stipulates the contrary. *51 Therefore, using undefined legal concepts (i.e., using natural language in a law) is acknowledged to be as inevitable as the need to interpret these concepts afterwards.

The Constitutional Review Chamber of the Supreme Court has asked that, in the process of interpretation, the interpreters turn their gaze to societal issues. If we transform the idea such that it meshes with the vocabulary used by the Tartu–Moscow semioticians, cultural issues come into play in finding of a meaning of a norm from aims expressed by the legislator – i.e., through the social as well as cultural context of a norm (that is, external reference).

The European Court of Justice too is ready to report on the common usage of words (natural language) and hence uphold the attribute of foreign reference. In accordance with said court’s settled case law, the meaning and scope of terms for which European Union law provides no definition must be determined by considering the usual meaning of the terms in everyday language, while also taking into account the context in which they occur and the purposes of the rules of which they form a part. *52

In conclusion, legal terms are always applied with an effort to maintain the core of the concept as accurately and to as great an extent as possible. At the same time, each case, in its new form, comprises legal terms with a new context of usage. In particular, the cases associated with changes in society that have never been considered in this connection in the past form the core of the norms (e-solutions, ‘digisociety’, various issues of minorities, refugee issues, etc.).

5. Conclusions

From one perspective, the idea of law as a secondary modelling system is in accordance with the conclusions drawn by TMS scholars with regard to other cultural texts. At the same time, it leads to conclusions similar to those articulated in theory of law.

If we look for a practical solution as output, for the interpretation of undefined legal concepts, a two-level test has to be passed: firstly, the meaning in natural language has to be found, and, after that, correction should be applied in accordance with the concept’s place in the legal system at hand, such that the law remains as constant as possible. From a broader angle, the place of undefined legal concepts in law under Lotman’s schema is important. Here, undefined legal concepts in legal systems are akin to elements of a language that ensure the deep memory of the system – these are, firstly, liable to change but, secondly, able to survive in the system, both in their invariance and in their variability. Undefined legal concepts have both of these characteristics: they possess certain autonomy, because they are not defined by law (surviving via connections to the surrounding law). At the same time, this is a distinctive feature, which leads to judges having the creative task of finding a fair solution (changing via shifts in meaning in natural language). According to Lotman, if we consider a series of synchronous contexts (in our case, many court cases), then not only can the stability of the element – the undefined concept – be made evident but so can the constant change due to the reading of the various dynamic codes. *53 The undefined legal concepts therefore function to bind the constantly modernising society and the law so that the latter does not fossilise.

In the context of language and words, Lotman concludes that one result of an attribute of liability to change is that one and the same element, penetrating the various levels of the system, interconnects these levels. *54 Undefined legal concepts interconnect elements of law in that their interpretation always leads to the question of what the legal system is like. As determined by case law, the interpretation has to follow the aims of the acts with which it forms a whole and be aligned with the broader context (the general principles of law etc.). This leads to a systematic approach to interpreting undefined legal concepts, through which the rule of law is ensured.

With the assistance of Lotman’s cultural semiotics, it is possible to formulate the regularities that operate in legal interpretation in the same way as in culture. These regularities, which have never before been pointed out in works of legal semiotics or legal theory, can be summarised thus:

1) In the legal domain, the relationship between the legal language and the natural language determines the degree of validity and comprehensibility of the law for the society. The further the legal language is from natural language, the greater the respect it engenders but also the less clear it is. Conversely, if the legal language is equivalent to the natural language, the law is going to be ineffective – the existence of extensive freedom for interpretation reduces the potency of the law.

2) Legislation and interpretation of law are opposite processes that together exist in a state of continual tension and mutual translation. *55 The interpreter of law must look for natural language (utterances) in the law, while the legislator must strive for legal language (text) from within natural language – that is, the language that best suits the existing legal system.

3) Every legal concept and, moreover, every legal gap is a reflection of the legal system, encompassing its condensed programme on the one hand (self-reference) and a reflection of the society on the other (external reference). The tension between the two is most evident in the interpretation of undefined legal concepts, in connection with which Estonian and European case law alike confirm that both need to be taken into consideration. On the one hand, undefined legal concepts and the legal gaps detected increase the coherence of society and law through legal elaboration; on the other hand, however, total openness to new material in the law leads to the law losing its validity for the society (see conclusion 1).

These three conclusions contribute to a well-functioning framework for interpreting legal concepts and overcoming legal gaps. In each case, it is necessary to define the ‘utterance’ and the ‘text’, clarify the ‘self reference’ and the ‘external reference’ in law, and bear in mind throughout the process that interpretation always occurs in relation to this binary structure.

Lotman’s interest in the effect of secondary modelling systems on the general system of culture clearly has its analogue in the field of legal studies. Just as much as a work of art is a secondary modelling system, so too is a carefully drafted contract or a curiously decided case of law, which, when studied in detail from the perspective of its linguistic elements, can reveal the worldview behind and suffusing it. *56

pp.3-11