Learning from Neighbours'Experiences: Property Law and Consumer Credit

22/2014

ISBN 978-9985-870-34-1

Issue

Analysis of the facts of the current situation in Lithuania with respect to the consumer-credit market clearly reveals that the market is rapidly developing, and some statistical data are thought‑provoking here with respect to the question of whether the state should take any measures in this connection (via stricter regulatory measures or other actions).

The article addresses several aspects of the consumer-credit landscape: it i) provides a general overview of the regulation of consumer credit in Lithuania; ii) examines the particular fields of regulation of consumer credit, taking into account, where applicable, the provisions specific to control of easy-access non-secured consumer loans extended via electronic means; ii) and offers analysis of the proposed amendments to the regulations on consumer credit that are now under discussion at the ministerial level.

Analysis of existing consumer-credit regulation in Lithuania reveals that, on one hand, even now there are some norms regulating the consumer-credit market that could protect the interests of consumers and prevent excessively easy access to non-secured consumer loans via electronic means – if applied effectively. However, the proposals made in the draft for amendments to the Law on Consumer Credit reflect a quite clear tendency toward tighter and more extensive regulation of the consumer-credit market. It seems that this regulation is not being undertaken understandably as the last resort; instead, it is only one option for the resolving of issues related to the consumer-credit market, and proper justification of such regulations remains absent. Moreover, some of the proposals (even for consumers) are extremely drastic. The author of this article is quite convinced that the problems of the consumer-credit market cannot be remedied through purely legislative means anyway, especially as the practical application of most of the legal norms suggested has not been tested. Rather, the state should take coherent extensive and systemic measures that could help to increase consumers’ conscientiousness, financial awareness, and financial literacy, with particular attention paid to young people who do not have enough experience in the management of their finances. Only a conscientious, financially literate society can be a counterbalance to the unfair commercial practices employed by many financial service providers. It is clear that supply quickly follows wherever demand exists, and the same can be said with regard to unfair commercial practices. Accordingly, what is the future of consumer credit? Quo vadis, consumer credit?

Keywords:

consumer-credit market; responsible lending; consumer-credit contract; consumer-credit lender; consumer

1. Introduction

The recent financial crisis raised a number of issues related to whether the Lithuanian state did everything it could to avoid dire financial consequences not only for individuals but also for society as a whole. The question was asked—and is still being raised—at both national and EU level of the steps that should be taken to ensure that avoidance of such crisis or mitigation of its consequences.

Consumer credit is one of the financial services provided not only by the banks but also by other parties: both credit institutions and legal persons that are not credit institutions. In consequence of the financial crisis, banks have tightened their conditions for the provision of consumer credit; therefore, the establishment of new companies providing consumer credit has been affected, as has the expansion of the consumer-credit market beyond the banks. Today‘s statistics, as will be shown below, clearly substantiate the fact that consumer loans are granted in a reckless manner, regardless of whether or not the consumer will be able to repay the loan.

In recent years, consumer credit (especially in the form of ‘quick loans’) has been intensively and aggressively marketed on television, in magazines, and via the Internet. Usually, attractive slogans are used to promote consumers’ activeness in the consumer-credit market. The marketing advertisements for consumer credit create the impression that consumer credit is the cure for all diseases and the easiest solution, a way to balance the consumer’s finances, while also highlighting the speed of granting a loan and the around-the-clock nature of the service, along with the fact that the consumer credit can be applied for via text messages or Web sites. Furthermore, the client may be attracted by the allure of the first consumer credit being free of charge etc.

The situation in Lithuania with respect to the consumer-credit market clearly reveals that the market is rapidly developing and some statistical data are thought-provoking here with respect to the question of whether the state should take any measures (via tighter regulatory measures or other actions). The 2012 overview of the consumer-credit market, along with the presentation on this topic *1 , announced by the Bank of Lithuania (hereinafter ‘the supervisory institution’) in July of 2013 revealed some important facts, which served as the basis for the supervisory institution’s proposal of some amendments to the consumer-credit regulations. According to the supervisory institution’s comparisons with 2011, in 2012 i) there were 70% more consumer-credit agreements signed, in an increase from 366,000 to 621,000 agreements; ii) the total amount of consumer credit granted was 32% greater, rising from 653.97 million litai (~189.56 million euros) to 862.31 million litai (~244.97 million euros); and iii) a 2.5 times increase was seen in the portfolio of small‑sum consumer credit: from 83.18 million litai (~24.11 million euros) to 206.91 million litai (~59.97 million euros). At the end of 2012, payment was overdue by more than 60 days for about 20% of consumer credit (with 29% of the cases involving small-sum consumer credit), 40.7% of the outstanding amount of consumer credit was accounted for by small-sum consumer credit wherein the repayment period had been extended after the borrower paid an extension fee, 35% of the clients for small-sum consumer credit were below age 25, and the average annual percentage rate of charge (APR) for small-sum consumer credit was 177%. However, only 44 consumer complaints had been made in 2012 to the supervisory institution regarding consumer credit. The supervisory institution announced this March its overview of the consumer credit market for 2013 *2 . According to the supervisory institution’s comparison with 2012, in 2013 i) there were 17.19% more consumer‑credit agreements signed (722,000 agreements); ii) the total amount of consumer credit granted was 16.67% higher, at 1,002.71 million litai (~290.64 million euros); iii) and there had been a 2.5 times increase in the portfolio of small-sum consumer credit, from 83.18 million to 206.91 million litai (~24.11 million euros to ~59.97 million euros). At the end of 2013, 23.6% of the consumer credit had its payment overdue by more than 60 days (32.7% of the associated credit being small-sum consumer credit), 36.81% of the outstanding amount of consumer credit came from small-sum consumer credit for which the repayment period had been extended after the borrower paid an extension fee, 39.21% of the clients for small-sum consumer credit were under 25, and the average APR for small-sum consumer credit was 164% (the APR has fallen by more than 10%). Despite the fact that the number of consumers filing complaints about consumer credit with the supervisory institution rose from 2012 to 2013, rising from 44 to 63, it seems—and the supervisory institution has arrived at the same conclusion—that this number is still relatively small. The conclusion of the supervisory institution in its evaluation of the 2013 consumer-credit market was that the consumer‑credit market is growing further.

Therefore, it would be meaningful to mention that the number of lenders clearly shows as well that the consumer-credit market is very much growing in Lithuania. The number of lenders (at least those that are included in the official lists of lenders) rose in the span of six months (from 31 December 2012 to the start of July 2013) to almost 300%: the number of lenders rose from 56 to 146. Despite the fact that at the time of this writing (30 April 2014), the number of lenders remains at a similar level (147 lenders are on the list of consumer-credit lenders), there is no reason to believe that the consumer‑credit market has not created even more issues for society.

The main aim of the present article is to show how the legal norms of Lithuania regulating consumer credit are dealing with the issue of easy access to non-secured consumer loans, especially via electronic means. The article also presents the proposals of the Bank of Lithuania pertaining to measures for improvement of the consumer-credit market situation with the aim of precluding ill‑considered conduct and incautious decisions of consumers, along with additional measures for control of the consumer-credit market.

However, it should be noted that neither the 2012 overview of the consumer-credit market and presentation on this topic nor the statistics on consumer credit in 2013 *3 released by the supervisory institution pay particular attention to the non-secured consumer credit that lenders provide via electronic means. However, as has been mentioned above, the supervisory institution in March released its overview of the 2013 consumer-credit market *4 , in which it indicated that, just as in the previous year (2012), most of the small-sum credit was provided by distance means (by phone or over the Internet). The supervisory institution indicated that 87.22% of the cases of small-sum credit were handled by distance means. However, the supervisory institution has not provided any information on whether and how the lenders follow the requirements of the laws on provision of information to consumers or other legal requirements, let alone examination of the factual situation.

This article addresses several aspects of the consumer-credit landscape: it i) provides a general overview of the regulation of consumer credit in Lithuania; ii) examines the particular fields of regulation of consumer credit, taking into account, where applicable, the provisions specific to control of easy-access non-secured consumer loans extended via electronic means; ii) and offers analysis of the proposed amendments to the regulations on consumer credit that are now under discussion at the ministerial level.

2. Overview of the regulation of consumer credit in Lithuania

2.1. A general legal overview of the regulation of consumer credit in Lithuania

Consumer credit is regulated by public and private legal norms. The regulation of consumer credit consists, in essence, of the regulation of particulars of consumer-credit contracts, the conditions imposed for lender (including credit intermediary) activity, and the responsibilities in cases of infringement of the requirements of the law. The legal basis for consumer credit has been influenced mostly by European Union law. Therefore, the relevant legal rules related to consumer credit were brought into the Civil Code of the Republic of Lithuania (hereinafter ‘the Civil Code’) *5 with the transposition of the old Consumer Credit Directive (CCD) *6 (articles 6.886–6.891 of the Civil Code, regulating the specifics of consumer-credit contracts, were included in the chapter ‘Loan Agreement’). However, the method of transposition of the new Consumer Credit Directive (hereinafter ‘Directive 2008/48/EC’) *7 into Lithuanian law was different: the separate Law on Consumer Credit *8 , regulating private- and public-law matters, was adopted, and the provisions of the Civil Code regulating consumer credit were revoked accordingly (only Article 6.886, which specifies just the definition of a consumer-credit contract, the obligation of a consumer-credit lender to ensure that the principle of responsible lending is followed, the definition of ‘consumer-credit lender’, and reference to regulation by other laws). It should be noted that, in general, the wording of the Law on Consumer Credit corresponds with the wording of Directive 2008/48/EC. It should be taken into account also that the draft of the law was subject to very lively discussion in the Parliament of the Republic of Lithuania and there were some proposals to establish stricter provisions than are set forth in Directive 2008/48/EC.

The Law on Consumer Credit was changed—new wording, adopted on 17 November 2011, came into force on 1 January 2012. The essence of the changes of the law involved, firstly, institutional changes, with the functions related to the public administration of the consumer-credit market being assigned to the Bank of Lithuania (before that, the State Consumer Protection Authority was responsible for the supervision of the consumer-credit market). The supervisory function, functions related to imposition of sanctions and the alternative dispute-resolution mechanism in particular, were assigned to the Bank of Lithuania as the supervisory institution. The institutional changes caused some changes in the penalisation procedure accordingly. It may be concluded that it was the right decision to move the supervisory functions related to the consumer-credit market to the Bank of Lithuania, as this institution is more closely linked to the market itself and, therefore, able to assess the consumer-credit market in a more general way, taking into account the whole financial market. That has enabled it to gain a better understanding of the problems that consumers might face. Secondly, there was a quite important modification in relation to the maximum APR, which was reduced from 250 to 200 per cent. It should be noted that the maximum APR set forth by law is presumed to be the fair annual percentage rate of charge, and an APR greater than 200% is considered unfair. Therefore, it can be concluded that the change in the law was generally in the interests of consumers. More detailed analysis is provided further on in the article.

It should be mentioned that some secondary legal acts that are important in the field of consumer credit were adopted also. The Bank of Lithuania, as the institution responsible for supervision of the consumer-credit market, approved the rules for calculation of the annual percentage rate of charge *9 , the principles associated with responsible lending and evaluation of consumer creditworthiness *10 , the rules for lenders’ inclusion on the list of providers of credit *11 (the latter rules were adopted by the State Consumer Rights Protection Authority and were not revised by the Bank of Lithuania), the guidelines on the advertisement of financial services *12 , and rules on the provision of the obligatory information to the Bank of Lithuania *13 . The new wording of the principles for responsible lending and evaluation of a consumer’s creditworthiness was adopted in 2013 (and came into force on 1 July of that year) (hereinafter, ‘the Principles’), receiving a very negative reaction from consumer‑credit lenders. The document was sharply criticised by some stakeholders (especially consumer-credit lenders and the association for small-sum consumer credit) in the media. They argued that this document had been adopted without thorough examination of the situation, that people will lose the possibility of receiving credit, that the new requirements will create a ‘black economy’ in this field, that the Principles are ambiguous, and that the document would be complicated to apply in practice. However, the banks welcomed the Principles and argued that they protect the client no matter who the lender is—a bank or another lender.

As has been illustrated above, the number of consumer-credit contracts has increased in recent years in Lithuania. The consumer-credit lenders have used aggressive marketing tactics; however, paradoxically, despite the fact that the Law on Consumer Credit has been in force for three years already, only a few cases related to consumer credit have reached the Supreme Court of the Republic of Lithuania (hereinafter ‘the Supreme Court’). Moreover, there are no cases that would be related to the issues of easy obtaining of non-secured consumer loans via electronic means. Since the rules provided by the Law on Consumer Credit have not yet been tested and have not been verified in court practice (at least Supreme Court practice); therefore, it is difficult to judge what particular problems might arise in the application and interpretation of the Law on Consumer Credit in the existing consumer-credit market.

The regulation of consumer credit could be discussed in detail in terms of the following aspects: i) the particulars of the consumer-credit contract, ii) the duty of disclosure (the obligation to provide information to the consumer) and requirements for the information to be provided to the consumer, iii) the obligation of the lender to evaluate the creditworthiness of the consumer, iv) regulation of the activity of the lenders of credit, v) the state institutions responsible for the consumer-credit market, and vi) responsibility related to infringement of the provisions of the law.

The ratione personae of the Law on Consumer Credit is defined by application to the B2C relationship. The parties to the consumer-credit contract are the consumer (or consumer-credit borrower) and the lender of consumer credit. The consumer (or consumer-credit borrower) is, according to the law, a natural person who is aiming to conclude a consumer-credit contract for personal, family, or household purposes, not business or profession needs. The notion of the consumer reflects the definition in Directive 2008/48/EC. Although some proposals were made by the association of small and medium-sized enterprises for inclusion in the definition of a consumer not only natural persons, with the definition expanded to cover small and medium-sized enterprises too, the Lithuanian legislator decided not to extend the personal scope of Directive 2008/48/EC. The consumer-credit lender is a person, though not a natural person, who grants or promises to grant consumer credit in the course of his business. As the definition of the consumer-credit lender is not fully harmonised and the Member States have discretion to decide on expansion of the definition of who is a credit lender, the legislator of Lithuania decided that the lender here should be defined as only a legal person. Therefore, a natural person may not provide consumer-credit services.

The material scope of the Law on Consumer Credit in general is the same provided in Directive 2008/48/EC. However, as Directive 2008/48/EC allows some deviations from the provisions of the CCD with regard to scope, the legislator has decided not to exclude those credit agreements wherein credit is granted free of interest and without any charges and credit agreements under the terms of which the credit has to be repaid within three months and only insignificant charges are payable. Accordingly, the law provides no exceptions for credit involving a total amount of credit less than 200 euro (defined as credit above a 200-euro limit). The reason for the deviations mentioned was to include quick credit within the scope of the law.

2.2. The duty of disclosure and requirements as to the information provided to the consumer

The regulation of the duty of disclosure covers three stages in the agreement process, and its regulation reflects the provisions of Directive 2008/48/EC: i) the obligation to provide information in the advertising, ii) the obligation to provide information before conclusion of the contract (i.e., pre-contractual information), and iii) the obligation to provide information by implementation of the contract (that is, in the contractual stage). It should be noted that, according to Directive 2008/48/EC, the disclosure of information in the advertising or some details in the pre-contractual stage should be implemented through a representative example; however, the Law on Consumer Credit where it addresses the advertising stage refers only to standard information. It does not stipulate the requirement that the standard information provide illustration by means of representative example *14 . In general, the regulation of the duty of disclosure reflects the regulation by Directive 2008/48/EC. The only difference is that the Law on Consumer Credit establishes the onus probandi rule, according to which proving of the provision of the information to the consumer rests with the credit-lender. Moreover, no particular regulation exists in the area of the duty of disclosure related to the control of easy access to consumer loans via electronic means *15 , and neither the Law on Consumer Credit nor the Law on Unfair Commercial Practice makes any particular provisions in this area.

From the factual situation and the proposals issued by the supervisory institution (which will be discussed later in the article), it seems that one of the important issues for effective implementation of control of the consumer-credit market is the relationship between the provisions of the Law on Consumer Credit and the Law on Unfair Commercial Practice *16 , especially as relevant for separation of the competence of the supervisory institution from that of the other institutions responsible for the application of the Law on Unfair Commercial Practice. This issue proceeds from European Union law and is linked to the relationship between Directive 2008/48/EC and the Unfair Commercial Practices Directive (UCPD) *17 . As the European Commission has explained, the relationship between the UCPD and the CCD should be resolved through the application of the principles of lex generalis and lex specialis *18 . Although the UCPD, regardless of its full‑harmonisation nature, allows Member States to provide specific regulation of financial services, the Lithuanian legislation does not state any specific provisions in the Law on Unfair Commercial Practice with respect to consumer credit. Part 3 of Article 4 of the Law on Consumer Credit indicates that the provisions of the Law on Unfair Commercial Practice related to the advertisement of consumer credit are applied where the rules of the Law on Consumer Credit are not. However, it seems that this rule does not help very much: firstly, as will be addressed below, the supervisory institution has indicated that ‘at this time, the supervising of advertising of consumer‑credit contracts is limited to checking the criteria of Article 4 (1) of the Law; therefore, it means in practice that this rule is rarely applied: the consumer-credit lenders do not state any credit‑related costs in advertisements, and advertising is limited to general resounding phrases’ *19 . It should be noted that three institutions have competence related to the control of provision or non‑provision of such information to the consumer, these being the supervisory institution (responsible for the control of the requirements under the Law on Consumer Credit), the Competition Council (generally responsible for the control of misleading advertisement according to the Law on Unfair Commercial Practice and the Law on Advertising *20 ), and the State Consumer Rights Protection Authority (responsible for the control of unfair commercial practices and of advertising that does not fall within the competence of the Competition Council). It becomes obvious from reviewing the practice of the Competition Council that the last of these institutions has not applied the provisions of the Law on Unfair Commercial Practice to misleading advertising with respect to consumer credit. The same is true of the Consumer Rights Protection Authority *21 . The supervisory institution has applied liability in accordance with the Law on Consumer Credit in only a handful of cases *22 . That means that said institution has not effectively applied the penalties related to infringement of the rules on the duty of disclosure in line with the Law on Consumer Credit. Such a situation is very interesting and strange, because the above-mentioned state institutions were, in the cases described by the supervisory institution, able to apply the provisions of the Law on Consumer Credit by imposing sanctions for infringement of the obligation to provide information to the consumer or the provisions of the Law on Unfair Commercial Practice by imposing sanctions for misleading actions or omissions. As has been stated by the European Commission, ‘the assessment of this compliance with the CCD and UCPD should be carried out, on a case-by-case basis, by the national authorities of the Member States which are primarily competent for investigating the conduct of individual companies in the light of EU legislation’ *23 . It is obvious that it may be hard in practice to separate the competence of three state institutions dealing with the enforcement of the provisions of the two laws. However, all of the problems (or, rather, at least most of them) could be solved via effective co-operation among these state institutions. Therefore, it is likely that the reason for the ineffective control of the consumer‑credit market is not a problem with the sufficiency of the legal norms (at least there is no evidence that the legal norms preclude the state institutions’ application of the laws mentioned) but the inefficient co-ordination of activities among the individual institutions responsible for control of the implementation of the Law on Consumer Credit and the Law on Unfair Commercial Practice. Undoubtedly, the effective application of the latter law could prevent unfair practices in the consumer-credit market and could be one of the measures used to control the ease of access to non‑secured consumer loans, including via electronic means.

2.3. Regulation of the consumer-credit contract

As has been mentioned above, the Law on Consumer Credit regulates the particulars of the consumer-credit contract and, in its manner of doing so, generally reflects the provisions of Directive 2008/48/EC. There are, however, several elements added in the Lithuanian legislation.

Firstly, the Law on Consumer Credit (in its Article 10) sets in place some provisions related to consumer-credit contracts concluded by distance means (it should be noted that these provisions are additional to the national regulation stipulated in the Law on Consumer Protection *24 with respect to the distance marketing of consumer financial services, which reflected the regulation in the EU directive on distance marketing of consumer financial services *25 ). The law refers to two conditions for the conclusion of a consumer contract by distance means: firstly, the law specifies the obligation of the consumer‑credit lender to ensure that the consumer wants to conclude the contract by distance means; secondly, the contract shall be concluded only if the lender has ascertained the identity of the consumer. This provision of the law should be one of the measures used to prevent easy access to consumer credit and to preclude incautious decisions by consumers as to whether or not to enter into a credit agreement. However, it is not clear how this legal norm functions in practice and whether the consumer-credit lenders follow the associated requirements of the law in the process of conclusion of their consumer-credit contracts. It seems, when one considers the discussion that has appeared from time to time in the media about persons whose names were used by others taking out consumer credit, that this obligation is not fulfilled in the correct manner. As can be concluded from the publicly available information, the supervisory institution has not punished any of the consumer lenders for such practices.

Secondly, additionally to the provisions of Directive 2008/48/EC, Lithuanian regulation establishes certain contractual remedies for application if the obligation to provide information to the consumer is breached by the consumer-credit lender; i.e., if the lender provides misleading or inaccurate information and this information formed the basis for the decision taken by the consumer, the consumer has the right i) to withdraw from the contract after 30 days’ notice or ii) to repay the credit in accordance with the conditions of the contract but without paying interest and any other fees. That is, the consumer has an obligation to pay only the principal of the loan, not any other amounts. The current content of the norm corresponds in essence with the regulation set forth in Article 6.888 of the Civil Code as it existed until the transposition of Directive 2008/48/EC. However, despite the fact that the above-mentioned norms have existed for almost 13 years now, there is no court practice of the interpretation of this regulation. Therefore, the practical effectiveness of the regulation is highly doubtful. One could conclude that consumers have not relied on this regulation and have not attempted to protect their rights on the basis of it. The rule mentioned appears at first glance to be very similar to the regulation of the consumer’s right to withdraw from the consumer-credit contract as specified by Directive 2008/48/EC. However, thorough analysis shows that the regulation is of a different nature, especially in its consequences for the consumer-credit lender. Firstly, the consumer’s right to withdraw from the consumer-credit agreement is not bounded by any particular amount of time. The fact of the provision of incorrect information to the consumer may be revealed at any time, whereupon the consumer may exercise his right to withdraw. Secondly, the right of withdrawal is related to reasons indicated by the law; that is, the grounds for exercise of the right of withdrawal consist of breach of the obligation of the consumer-credit lender to provide information to the consumer. Thirdly, the regulation of the right of withdrawal means the imposition of sanctions of some kind on the consumer-credit lender because the consumer has the right to pay only the principal and not pay any other fees. Moreover, the consumer is obliged to pay the amount of the principal only in parts, as provided for by the contract (according to the schedule referred to therein). However, it is not clear whether these consequences are to be applied only after withdrawal from the contract or whether they influence payments made before the withdrawal as well. The analysis provided above shows that the regulation pertains to the right of the consumer to terminate the contract; however, the regulation is not very consistent, because this right is associated not with breach of obligations under the contract but with the obligations that existed in the pre-contractual stage. Moreover, this regulation is not co‑ordinated with the regulation of control of unfair terms: where there exist circumstances in which misleading information was provided to the consumer, it suffices to conclude that unfair terms existed in the contract and the contract is null and void, with there being no necessity of terminating the contract explicitly.

Thirdly, the law establishes a maximum rate of interest on default, which shall not be higher than 0.05% for each day of default. Moreover, the law states the imperative norm that any other interest or fees for default shall not be paid by the consumer in the event of non-fulfilment of obligations under the consumer-credit contract. Therefore, in this case, the law restricts the liability of the consumer in what corresponds with the general principle of civil liability set forth in Part 1 of Article 6.251 of the Civil Code. Moreover, according to Part 2 of Article 6.73 of the Civil Code, the court has discretion to reduce the interest on default *26 , though the amounts of interest already paid on default cannot be reduced.

Fourthly, the law gives an exhaustive list of conditions in which the lender is able to terminate the contract. These conditions must all exist in order for termination to apply. The lender is able to terminate a consumer-credit contract only if i) the consumer has been informed about the payment related to default, ii) payment is delayed by more than one month and in the amount of not less than 10% of the total amount of the credit or delayed for longer than three consecutively months, and iii) the relevant payment has not been made within two weeks from additional notification to the debtor.

Fifthly, the law establishes a prohibition of a lender of consumer credit accepting bills of exchange, cheques, and debt instruments as payment. In the event of breach of this prohibition, the lender shall indemnify the debtor from all damages related to further use of such means. However, the consumer‑credit lender is allowed to accept bills of exchange, cheques, and debt instruments as the means for security of the fulfilment of the obligation.

A sixth element has to do with one of the most important aspects of regulation of the consumer contract, related to regulation of consumer-credit prices and the maximum limit for the annual percentage rate. Firstly, the law specifies a set of principles applicable to the total cost of the credit to the consumer. According to the law, the total cost of the credit for the consumer has to be reasonable, justified, and in line with the fair dealing principle, and it must not infringe the balance between the interests of the consumer‑credit lender and the consumer. Secondly, the law establishes the presumption that the total cost of the credit to the consumer does not correspond with the above‑mentioned principles if the APR at the time of conclusion of the contract exceeds 200%. That means that the law regulates limits to the APR (via a cap on the APR). Setting of a maximum APR usually is used as a measure under anti-usury legislation *27 . It should be noted that many countries in the European Union have regulations according to which the price associated with a consumer‑credit contract is restricted by one or another method *28 . Several issues could be mentioned in this connection with respect to Lithuanian regulation. Firstly, it is not clear enough what consequences are to be applied if the mentioned requirements of the law are infringed. It is clear that the law provides for only one consequence—with the presumption of the unfairness of the consumer price if the conditions of the law are not met. However, it should be noted that the control of unfair terms is not applied to the main terms of the agreement, with the exception of application of the transparency test (i.e., Lithuanian regulations establish the principle set forth in the Unfair Terms Directive). Therefore, there is not any basis in the general rules of the Civil Code for control of the main terms of the agreement or for declaring them unfair. That means that the regulation setting an APR cap is not co-ordinated with the Civil Code’s provisions and is not complete. Secondly, it is not clear what state body would have the competence to indicate whether a contract term is fair or not and what price is fair in any given situation. Presumably, the courts would have competence to decide on this matter. However, in this case, one could debate what legal grounds exist for the court to interfere in the private (contractual) relationships and to decide on the contract price in particular, taking into account the principle that the court is able to intervene in the contractual relationship only in the cases specified by the law. However, such particulars are not described by the Civil Code. One might consider whether Article 6.228 could be applied in this situation *29 or whether general grounds for nullity of the transactions could be applied—e.g., declaring the contract null and void because it is counter to public order and good morals. The regulation of APR limits could lead to very different consequences under the above-mentioned articles of the Civil Code; therefore, it is not clear what kinds of consequences were intended upon the legislator’s inclusion of the mentioned provision in the Law on Consumer Credit. Moreover, as has been mentioned above, there is a lack of court practice addressing this matter and it is difficult to predict how the law might be applied and interpreted by the court.

As has already been mentioned, besides special provisions of the Law on Consumer Credit, general provisions of the Civil Code regulating contract law and, in particular, the legal norms regulating the control of unfair terms are applied to consumer-credit contracts. Obviously, aggressive advertising practices should in practice be deemed to lead to the use of unfair contract terms. Accordingly, there should be a presumption of a need to apply the rules on unfair terms; however, again, there is practically no associated case law. In one of the most recent court decisions—the decision of 3 January 2014 *30 in which the Supreme Court dealt with the terms of a contract with regard to the fairness of contractual interest—the court, stating that the applicant did not challenge the interest rate and contested only the contract term dealing with determination of interest, addressed the fairness of the contract solely in this respect. It should be noted that the court did not take into consideration the principle that it itself had developed in line with the practice of the European Court of Justice (ECJ) according to which the court must ex officio determine the matter of unfair terms of consumer contracts *31 . For the following reasons, the court did not declare the relevant term of the contract unfair: Firstly, in the court’s opinion, the clause in question could not have been a surprise clause, in view of its content, wording, and method of expression (its content was expressed not only in the standard terms but also in the part of the contract discussed case‑specifically, which covered the following: the yearly interest rate on the amount of the credit, the total amount of the credit, and the payment schedule (which reflected the monthly amount of credit to be repaid and the interest rate for the amount of credit granted); the method of calculation was indicated unambiguously, in clear verbal expression, and the method of payment was specified in a prominent place). Secondly, the court took into account the specific personal characteristics of the debtor, including the fact that the person had a higher education and, therefore, could be deemed legally educated and aware that, in consideration of the opportunity to get a loan rapidly, a higher interest rate is charged *32 .

2.4. The lender’s obligation to evaluate the creditworthiness of the consumer

The Law on Consumer Credit establishes the obligation of the consumer-credit lender to evaluate the creditworthiness of the consumer. The law does not indicate any particular rules for individual types of consumer credit—for example, credit by text message (SMS credit) or quick credit. Although the principle of responsible lending is stated in the law, the content of that principle is not described there. However, the content is elaborated upon in the Principles. Accordingly, each lender has an obligation to adopt the rules on the evaluation of the consumer’s creditworthiness. Each lender of credit has an obligation to collect information (documents) proving its fulfilment of the obligation to evaluate consumer creditworthiness. The onus probandi lies with the lender for proving that it follows the requirements of the law.

The Consumer Credit Law regulates the consequences in the event that the credit-lender does not properly evaluate the creditworthiness of the consumer. In that case, the interest rate applied for late payment and any charges payable for default do not apply if the delay in payment arises from circumstances that were not properly evaluated. In the manner that this article examines below, the supervisory institution has suggested harsher consequences of the credit-lender breaching the obligation to evaluate the creditworthiness of the consumer properly.

As has been mentioned above, the principle of responsible lending has been elaborated upon by the supervisory institution. Under the Principles, responsible lending is understood as a lending activity of the lender during which consumer credit is granted in observance of certain provisions that create preconditions for the proper assessment of the consumer-credit borrower’s creditworthiness and precluding the consumer’s possible assumption of the burden of excessive financial obligations. Therefore, though the principle of responsible lending might be treated very broadly even at the level of the business culture, the content of this principle under Lithuanian legislation is reasonably specific. The content of the principle of responsible lending as set forth in the Principles has four aspects, which are now described in summary.

Firstly, the Principles specify an obligation of the lender to assess the creditworthiness of the consumer. The lender has to make this assessment on the basis of sufficient information. The lender must examine all material factors objectively expected to be relevant, in consideration of the information provided by the consumer and available to the lender that might affect the consumer’s creditworthiness—in particular, the sustainability of the consumer’s income, the credit history of the consumer, and potential changes (growth or reduction) in income. Accordingly, the Law on Consumer Credit and the Principles establish the obligation of the consumer to provide information to the lender. The lender is not responsible for consequences of a consumer’s provision of misleading or inappropriate information; under the Law on Consumer Credit and the Principles, the lender is obliged to check all information from the data sources available to it in observance of the requirements of the law, including the requirements of data protection. It should be noted that there is no official register of debtors or debts in Lithuania. Only private persons have managed such registers, which are negative registers. In addition to the general regulation in the area of data protection, there are no special rules on the collection of data about consumer credit, debts, or debtors in the Law on Consumer credit or in the Principles.

Secondly, the lending shall be based on the debt-to-income principle. In its evaluation of the consumer’s income, the lender should take into account the income of the consumer’s entire household, including current and future income. The core element for evaluation is sustainable income, which is described as the income of the consumer that can be reasonably expected throughout the time for which the consumer credit is granted.

Thirdly, the Principles refer to the debt–to-income ratio. Upon conclusion of the contract, the consumer’s average instalment for repayment of the principal and payment of interest, which is calculated by division of the sum of all repayments of the principal amount and of interest by the number of instances of payment during the credit period, shall not exceed 40% of the sustainable income of the consumer. This ratio covers all obligations to financial institutions. As has been mentioned above, this ratio has been much criticised by credit‑lenders.

Next, the creditworthiness of the consumer should not be assessed in only an abstract way. The aim of the assessment is to judge the ability of the consumer to assume the specific financial responsibility that, jointly with other financial responsibilities, the consumer would be able to fulfil. Therefore, the lender shall assess to some extent whether the financial product in question in any given case corresponds to the consumer’s needs and interests.

The Principles, though the law itself does not, state accordingly that promotion of irresponsible lending is forbidden.

When one considers the definition of responsible lending provided and the key foundations specified for ‘responsible lending’, one can conclude that, in the Lithuanian regulatory environment, responsible lending encompasses provision of advice rather than provision only of information and/or explanations to the consumer. As the European Commission stated in the Public Consultation on Responsible Lending and Borrowing in the European Union *33 , providing advice is distinct from providing information. The purpose of the provision of information is to describe the product, whereas the purpose behind providing of advice is to give a recommendation to the consumer in account of the particular circumstances of the consumer. Obviously, the Principles empower the credit-lender to assess the situation of the relevant consumer, considering not only information related to him but objective factors such as economic matters as well. Moreover, a negative result of the assessment leads to the lender’s obligation not to grant credit to the consumer. That means that the lender to some extent takes responsibility for the decision of the consumer. However, it is not clear how the Principles can work in practice, because the lender of consumer credit cannot, in principle, be an objective adviser, since that company is very much interested in the provision of service. At present, it is difficult to judge what kinds of consequences would be applied in court practice if, despite a negative assessment, a lender takes into account the consumer’s wishes by granting the credit and the consumer, because of insolvency, proves unable to repay that credit, especially in addition to the consequences discussed later in this article.

2.5. Regulation of the activity of lenders

The Consumer Credit Law established some requirements for activity of lenders of credit and credit intermediaries. These persons are allowed to provide consumer-credit services only after inclusion on an official list. Two separate such lists exist in Lithuania—one of credit-lenders and the other of intermediaries. The supervisory institution is responsible for the management of these lists and has the obligation to delete persons from the lists if the circumstances described below exist. However, it should be noted that the conditions for inclusion on a list are not strict and are rather more general than very specific in relation to ex ante control of the activity of the lender or intermediary. A legal person wanting to be included on the list shall submit to the supervisory institution the relevant request, information about public registers in which the supervisory institution will be able to check information about that legal person, the rules to be used for evaluation of the creditworthiness of consumer-credit borrowers, the rules to be used in the examination of complaints from consumer‑credit borrowers, and information about the databases wherein the creditworthiness of consumers will be checked, along with the list of consumer-credit intermediaries to be used, if the consumer‑credit lender intends to use the services of any.

Persons can be deleted from the list only if it later becomes clear that the person has provided inaccurate data or has not provided the information required by law. In summary, the regulation of credit-lenders’ activities does not seem to create much added value for control of the credit market.

There is no specific legislation in the area of debt collection. Therefore, it remains for the agreement between the lender and the collection company to determine how much the services should cost and what conditions for the provision of the services should be applied. Accordingly, it is up to the consumer-credit lender to decide whether he is willing to pay the costs related to debt collection.

2.6. The state institutions responsible for the consumer-credit market and their responsibility

In general, three state institutions can be distinguished as responsible for management (that is, supervision) of the consumer-credit market: i) the supervisory institution; ii) the Consumer Rights Protection Authority, and iii) the Competition Council.

The supervisory institution shall monitor the entire financial sector and, as has been noted above, has since 2012 been responsible for consumer protection in the consumer-credit market. This institution is responsible for the control of the implementation of the requirements of the Law on Consumer Credit. Moreover, according to Lithuania’s laws, the supervisory institution implements also the functions related to the alternative dispute-resolution mechanism. The main regulations for the alternative resolution procedure are established by a separate law regulating the activities of the Bank of Lithuania. Therefore, the Law on Consumer Credit does not specify detailed rules for the alternative dispute-resolution procedure; it only provides reference to the procedure regulated by the Law on the Bank of Lithuania. In summary, the following functions of the supervisory institution can be distinguished with regard to the consumer-credit market: i) supervision (management) of the entire financial market, ii) the control of the requirements of the Law on Consumer Credit; iii) the regulatory function, iv) the application of the penalties addressed in the Law on Consumer Credit, and v) the function of the body for the alternative dispute-resolution scheme.

The responsibility of the Consumer Rights Protection Authority is focused on the protection of consumer interests. This responsibility encompasses both the general function of co-ordination of the consumer-protection policy (along with the activity of the institutions active in the field of consumer protection) and particular functions related to some specific aspects of consumer protection. Two of the latter functions are relevant to the control of the consumer-credit market—namely, the Consumer Rights Protection Authority’s competence to control unfair terms and the competence to control unfair commercial practices and the advertising used. The latter competence is shared between the Consumer Rights Protection Authority and the Competition Council.

The Competition Council is responsible for controlling misleading advertising in accordance with the Law on Unfair Commercial Practice and the Law on Advertising.

One could conclude that the responsibility in the area of finance and credit matters has been divided among several institutions; however, the main role is assigned to the Bank of Lithuania. Moreover, it is more than clear that smooth co-operation among the three institutions is the main prerequisite for effective control of the consumer-credit market. However, as this article makes explicit, it is obvious that this co-operation is not ensured in Lithuania.

2.7. Regulation of the responsibility for handling infringement of the provisions of the law

The Consumer Credit Law specifies the economic sanctions (public-law sanctions) for the breach of requirements of the law (which regulates penalisation procedure). According to the law, the following sanctions can be imposed: i) warning for minor infringements of the law, ii) a penalty of 1,000 to 30,000 litai (~290 to ~8,700 euros), or iii) a penalty for repeated infringement within the span of one year—up to 120,000 litai (~34,800 euros). However, the law does not state criteria for the application of the sanctions. It employs only very general language, stating that ‘for the infringements of the provisions of this law the penalty is applied’. Therefore, the supervisory institution has the discretion to decide what sanctions shall be applied for particular infringements of the law. Moreover, as the law has not described the particular disposition of the infringement, sanctions could be applied for various types of breach of the law on Consumer Credit—for infringement of the duty to disclose, the obligation to assess the consumer’s creditworthiness, etc.

2.8. Enforcement related to consumer credit

The supervisory institution has indicated, in its 2012 and 2013 overviews of the consumer-credit market, discussed earlier in the article, that the most popular means of security for the consumer obligation is the bill of exchange. That means if the consumer has not repaid the debt, a simplified procedure is applied for the enforcement of the debt (the consumer-credit lender is able to refer the matter to a notary and the notary’s deed is the enforceable document that can be presented to a bailiff for the enforcement procedure). Therefore, the courts are not involved in this simplified procedure. In this case, the consumer does not have a practical opportunity to contest the debt.

It should be noted that the possibility has existed in Lithuania to apply simplified procedures in court for the enforcement of the debt (the procedure for issuing of a court order and the documentary proceedings). The same procedure can be used in the case of enforcement of the debt arising from a consumer-credit agreement. However, there are no publicly available statistics on how many disputes related to consumer credit have been resolved via the simplified procedure *34 .

3. The future of the regulation of consumer credit in Lithuania: Quo vadis, consumer credit?

The supervisory institution, relying on the analyses mentioned in the introduction to this article, has determined that the reasons for growth in consumer indebtedness are i) insufficient evaluation of consumer creditworthiness, ii) aggressive and misleading advertisements, and iii) non-responsible lending (lack of consumer education). Therefore, it has proposed certain measures for improvement of the situation: firstly, regulatory measures (which will be described below) and, secondly, educational measures—i.e., further development of the consumer-education system in the field of consumer credit. However, the supervisory institution has not suggested any particular measures related to education of consumers that could address the situation in the consumer-credit market today.

In October 2013, the supervisory institution submitted a draft to the Ministry of Finance for amendments to the Law on Consumer Credit *35 (hereinafter ‘the Draft Law’). The essence of the proposed amendments is described below.

Firstly, the supervisory institution has proposed tightening the regulation of the control of advertisement of consumer credit. As the quote above shows, the supervisory institution stressed in the explanatory note to the Draft Law *36 that consumer-credit lenders have not indicated the expenses related to their consumer credit in the advertisements of that credit and have usually used only resonant rhetoric. The Draft Law stipulates several amendments addressing this situation: i) there is an added requirement that the information be provided in a representative example (actually, this amendment involves correct transposition of the CCD); ii) the right to flesh out the requirements for advertisements of consumer credit is assigned to the supervisory institution; and iii) the supervisory institution is given the right to forbid misleading, ambiguous, and wrong advertising and, if necessary, the right to oblige the lender to deny of the credit advertised. However, it is very doubtful whether this additional regulation can achieve its aim, because, as noted above, the current issue is related rather more to inefficiency in the activity of the state institutions than to inefficiency of the legal norm.

Secondly, the supervisory institution has suggested shifting from ‘soft regulation’ to mandatory evaluation and has proposed inclusion of an obligation for the consumer-credit lender to check the consumer’s creditworthiness against databases (e.g., the social security database, SODRA) or other sources. The supervisory institution has indicated that current regulations allow lenders to rely on the information provided by the consumer—that is, information not supported by any evidence. The supervisory institution has suggested stricter consequences for breaching the above-mentioned obligation of the credit-lender: if the lender does not properly evaluate the creditworthiness of the consumer and if the circumstances that were not properly evaluated cause late payment, not only the interest on late payment and any charges payable for default shall not apply; neither shall the contractual interest charges apply. In that case, the consumer-credit lender would be allowed to require only that the consumer repay the principal sum of the credit. This proposed legal norm creates several problems. Firstly, the wording of the norm has not been drafted in a precise manner http://www.lb.lt/n22037/projektas.pdf (most recently accessed on 30 April, 2014) (in Lithuanian)."> *37 . The reference to the contractual interest charges is not very precise, and the wording gives the impression that it covers penalty interest for breach of contractual obligations rather than contractual interests. The conclusion that the regulation addresses the contractual interest charges and not other type of interest can be drawn only from the clarification provided in the explanatory note, not from the language itself. Secondly, the Draft Law stipulates a very different type of consequences for breach of the obligation of properly evaluating the creditworthiness of the consumer. The non-application of the interest on default should be treated as particular grounds for exemption from liability of the consumer as provided by law (Part 9 of Article 6.253 of the Civil Code of Lithuania stipulates that other grounds for exemption from civil liability or for non‑application thereof may be established by law or by agreement between the parties). However, the consequence linked to non-application of the contractual interest and other fees is not related to the liability of the credit-lender. The nature and essence of said consequence and what kind of private-law rules shall be applied for this consequence should be considered. Undoubtedly, both the interest under the consumer-credit contract and the loan principal are a matter of the agreement between the credit-lender and the consumer. The contractual interest is the monetary price (compensation to the lender) to be paid by the consumer for the product—i.e., for the loan. The consequence mentioned above would result in the service of consumer credit becoming free for the consumer. It must be noted that, while at first glance it would seem that the regulation establishes a consumer-credit lender’s liability for failing to assess consumers’ creditworthiness, the consequences specified are not related to the damages for the debtor, because it is not required that the consumer prove any damages and it is not clear whether the law requires that any even have been incurred. In such a case, the possibility of not applying the contractual interest proposed in the draft legislation should be interpreted as an exemption from fulfilment of part of the principal obligation. However, the Civil Code does not establish the option of regulation by other laws the ways of exempting the debtor from fulfilment of the principal obligation. Article 6.129 of the Civil Code only establishes the right of the creditor to decide on the exemption of the debtor. On the other hand, the legislator’s intervention with the principal obligation would mean interference with freedom of contract and, to some extent, with the regulation of the price of the contract. It is clear that applying such a consequence for inaccurately assessing the creditworthiness of a consumer would cause the consumer-credit lender to incur losses. Thereby, the regulations establish certain sanctions for the consumer-credit lender. With the norm interpreted in such a way, the question arises of whether the sanctions established by the legislator and the intervention in contractual relations are adequate and proportional, particularly in light of the fact that in this case a situation exists wherein there is no reason to consider the main content of the contract unfair *38 (if there were grounds to apply control of unfair terms, the relevant term of the contract would be considered unfair and thus be rendered void, such that there would be no basis for applying the consequences detailed in the norm analysed) . Thirdly, the mechanism for application of the norm is completely unclear—it is unclear whether it must be applied from notification of the consumer onward or retrospective too (e.g., is there a right to enforce the interest paid?) or whether the decision on this is left to the court’s discretion. Such uncertainty implies without doubt that either the norm will not be applied in practice or it will create uncertainty in case law applying and interpreting it. Either way, the norm is toothless, since i) it would be difficult to protect consumers’ interests and ii) even if they could be protected, this would take a marathon of court proceedings. The fact that such a norm is unclear and difficult to apply in practice can be seen also from the above-mentioned norm dealing with the consequences for not properly disclosing information to the consumer. Accordingly, it must be assumed that norms of this kind should be re-evaluated and either eliminated or revised into clear and consistent rules that would take into account basic civil-law norms and that could be properly applied in practice.

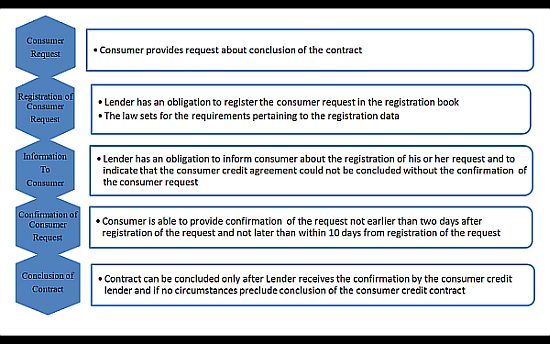

Thirdly, the supervisory institution has reconsidered the rules on conclusion of a consumer-credit contract. The Draft Law provides for a ‘cooling-off period’ before conclusion of the contract—two days at minimum and up to 10 days (a time frame designed for informed decision by the consumer). That means that a consumer-credit contract may be concluded only after confirmation of the request of the consumer to conclude the contract, given only after two days have elapsed from registration of the consumer’s request by the consumer-credit lender but not later than 10 days from registration of the consumer’s request to conclude the contract. If the Draft Law gets adopted, conclusion of a consumer-credit contract will consist of several stages. These are depicted in the diagram below.

The cooling-off period in consumer-protection law means that the consumer is able to withdraw from the contract within a particular period of time without any consequences arising for him. The cooling-off period introduced in the Draft Law has different consequences, though the aim of both is the same—to enable the consumer to change his mind within the time specified by law. Several issues related to the above-mentioned new rule can be highlighted. Firstly, it is not clear what the purpose is behind the maximum 10-day period set forth for confirmation of the consumer’s request to conclude the contract. Secondly, the Draft Law does not specify the consequences of the contract not being concluded by way of breach of the above-mentioned rule. Two types of consequences could be considered: the first interpretation involves considering the contract not to have been concluded in this situation, and the second way of interpreting matters is to argue that the contract was concluded but is null and void because it was concluded in breach of the imperative rule (see Article 1.80 of the Civil Code). In view of the general rules of contract law (including rules in the Civil Code that pertain to transactions), there is more justification for the first interpretation.

Undoubtedly, the proposed regulation related to formalisation of the procedure for the conclusion of a consumer-credit contract and the cooling-off period set forth by law will influence the speed of the process of the conclusion of consumer-credit contracts and, therefore, restrict consumers’ abilities to conclude the contract in an especially easy way. It is very likely that these new rules will create additional conditions aiding the consumer in rethinking the decision, and it is probable that in many cases the consumer will not confirm his wish to conclude the contract. However, the ultimate influence on the market for consumer credit will depend very much on the control of the implementation of this rule by the supervisory institution and on the rule’s application in court practice.

Fourthly, there is a proposal to reduce the APR from 200% to 50%. It should be noted that several members of the Parliament of the Republic of Lithuania proposed reduction of the APR to 36%. In late 2013, the Government offered its opinion *39 on the draft amendments to Article 21 of the Law on Consumer Credit, indicating that the complexity measures shall be used to solve the problems related to the consumer‑credit market and that the Government would issue a draft set of amendments to the Law on Consumer Credit at the beginning of 2014. However, at the time of this writing, the Government still has not provided the Parliament with such a draft. Also worthy of mention is that an interesting opinion on the above-mentioned draft has been provided by the European Law Department of the Ministry of Justice. That department indicated that the proposed legal norm raises doubts with respect to conformity with articles 56–62 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union *40 ; it stressed that stating a maximum APR, which encompasses all fees related to issuing of credit and its administration, restricts a person’s right to free movement of services. Such ex ante control may be justified only by public interests such as consumer protection. Moreover, it should be ascertained whether such a control system is relevant and strictly proportionate to the aim to be achieved and whether that aim cannot be reached by less restrictive means. On one hand, attention should be paid to the arguments of the European Law Department. Although the ECJ in SC Volksbank România SA v. Autoritatea Naţională pentru Protecţia Consumatorilor—Comisariatul Judeţean pentru Protecţia Consumatorilor Călăraşi (CJPC) *41 decided that restrictions to the number of bank charges do not fall into the category of restriction to free movement of services, it may be concluded that such a conclusion would not apply if the restrictions were of such a nature that the amount of charges or the interest rates were limited. Therefore, it might be that limitations to the APR would be considered by the European Court of Justice to restrict the free movement of services. On the other hand, as has been mentioned elsewhere in this article, the fact that many member states of the European Union have one or another restriction to the prices of consumer credit should be taken into account accordingly.

Fifthly, the supervisory institution has proposed regulation of the restrictions applied to conclusion of consumer-credit contracts: firstly, a consumer can restrict his rights himself by submitting a request to the state institution for prohibition of concluding a consumer‑credit contract. This request would be registered in a specific register, and consumer-credit lenders would be obliged not to conclude a contract with people whose requests are included in the register; secondly, the law would enable the courts to take a decision on restrictions/prohibition of a person’s capability of concluding a consumer-credit contract.

The above-mentioned proposals raise many legal doubts and questions regarding the adequacy and proportionality of the proposed measures. First of all, from a legal point of view, the nature of the proposed restriction is unclear. If this restriction is considered a limitation to a natural person’s active civil capacity, then such restriction does not comply with the mechanism for restricting active civil capacity that is established in the Civil Code of the Republic of Lithuania. It must be noted that Lithuania’s civil code does not permit establishment of only certain (specific) restrictions to a natural person’s active civil capacity, whether in whole or in part (in other words, the content of the rights is determined by law and applies in all cases equally). In addition, in the event of incapacity of a natural person, the guardian conducts transactions on behalf of the incapacitated person, and if there are restrictions to a person’s active legal capacity, that person may conclude legal transactions only with the consent of his guardian (with certain transactions permitted without the consent of the guardian). The proposed restrictions, in contrast, establish an absolute prohibition of concluding only one type of transactions—that of a consumer-credit contract. Secondly, the bases and criteria for such a restriction’s application are unclear. The proposed amendments establish a single, abstract criterion for application of the prohibition—abuse of the right to conclude consumer-credit contracts—and the prohibition does not establish any other criteria for application, including criteria for determining whether there is an abuse of rights and what evidence could confirm the existence of such abuse. It must be noted that the general provisions establishing restrictions to active legal capacity imply application of criteria whereby both legal circumstances and facts must be determined on the basis of opinions of medical experts. With the restriction at issue here, it is doubtful that medical experts could ascertain a person’s abuse of the right to conclude consumer‑credit contracts. Thirdly, the consequences of breaching this prohibition are unclear: would the contract concluded after abuse has been determined be void, or it could be later approved in some way?

As has already been noted, such restrictions raise doubts with respect to their proportionality. It is worth mentioning that even in cases of such activities as gambling and lotteries, there are no restrictions this strict established under Lithuanian legislation. Moreover, although it is obvious that the restrictions proposed by the supervisory institution reflect the proposals of the consumer organisations *42 , it seems clear that proposals made by the supervisory institution not only must be more measured and better reasoned from the legal point of view but also must be adequate for addressing the actual situation of the consumer-credit market. Additionally, it must be determined whether the situation in the consumer-credit market is temporary (such assessment processes were not observed); the court proceedings for restriction of natural persons’ active civil capacity would definitely take time, so doubts could be raised as to whether the restrictions would be relevant after a certain amount of time. In addition, the practice of using specific legislation to establish grounds for restriction of natural persons’ active civil capacity is defective since it may cause a situation wherein the government proposes restrictions of one’s rights related to specific transactions in the event of even the slightest market failure (in analogy, from a historical point of view, ought the government to have restricted rights to conclude mortgage transactions in order to minimise the consequences of the financial crisis?). With respect to the above-mentioned circumstances, the utility of the proposed amendments to the Law on Consumer Credit (in particular, with regard to the courts’ rights to prohibit conclusion of a consumer-credit contract) is highly debatable.

Sixthly, the supervisory institution has proposed the stipulation of additional condition on the activity of consumer-credit lenders—the chief executive officers and all natural or legal persons or related persons who, directly or indirectly, own 20% or more of the voting rights or authorised capital, along with all others who, in light of the articles of association or contracts concluded with the consumer-credit lenders or otherwise in the opinion of the supervisory institution may have a decisive influence in the operations of the consumer-credit lender, have to be of impeccable reputation. If the supervisory institution considers any of the above-mentioned persons not to be in compliance with this requirement, it shall have the right not to include the consumer-credit lender in question on the list of creditors or to remove it from the list. As is mentioned above, the current regulation of consumer-credit lenders’ operations and of the conditions under which a creditor may be included on the creditor list is laconic and does not create unnecessarily restrictive conditions to the operations of consumer-credit lenders. However, there is no doubt that the proposed amendments establish tighter restrictions. If the truth be told, it is not entirely clear whether the above‑mentioned norms would apply to those consumer-credit lenders that were on the creditor list before the amendments come into force. If such restrictions were not to be applied retroactively, they would have almost no consequences, since the second half of 2013 and the start of 2014 saw the number of consumer-credit lenders remain nearly constant, as was noted in the introduction to this article.

Seventhly, the supervisory institution has suggested increasing the penalties for infringement of the Law on Consumer Credit (for infringement, 5% and then for repeated infringement 10% of the organisation’s income from the consumer-credit services and deletion from the list of service providers).

In light of the above-mentioned insights into the Draft Law, there is only one major question that begs to be raised—quo vadis, consumer credit? The proposals made in the Draft Law reflect a quite clear tendency toward more extensive regulation of the consumer-credit market. It seems that this regulation is not being used understandably as the last resort; it is only one option for the resolving of issues related to the consumer-credit market, and proper justification of such regulations remains absent. Moreover, as has already been mentioned, some of the proposals are extremely drastic. The author of this article is quite convinced that the problems of the consumer-credit market cannot be remedied through purely legislative means anyway. Therefore, it is time to ask ourselves what the role of the state should be and where the boundaries for the consumer-credit market’s regulation should lie. Should the state be an active regulator, or should it shift its activity toward education measures or other actions, such as further development of a financial advisory services system or creation of alternative means allowing poor people to receive credit (e.g., ‘social credit’)? One might argue that the state should be only a passive observer and should not interfere in a market; however, this author does not suggest such an approach. Rather, the state should not concentrate purely on regulation measures in its activity (especially, regulation of a prohibitive nature); before that, it should take coherent extensive and systemic measures that could help to increase consumers’ conscientiousness, financial awareness, and financial literacy, with particular attention paid to young people who do not have enough experience in the management of their finances. The state should not shift the full burden of responsibility to the consumer lenders; it needs to take a very active role itself, especially in the field of consumer education. It is quite clear that the prohibitions and regulatory measures suggested cannot yield positive results if the society’s level of financial awareness and financial literacy remains relatively low. The necessity of increasing financial literacy has been stressed by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). The OECD has pointed out that consumers’ difficulties with making long‑term informed financial decisions and selecting financial products that match their needs may have negative consequences not only for individuals’ and households’ future financial well-being but also for the long-term stability of entire financial and economic systems *43 . To be fair, one should point out that the National Consumer Protection Strategy for 2011–2014 *44 indicated that it takes a long time to nurture consumers’ capabilities in this regard and, therefore, in order to foster these capabilities among Lithuanian consumers and for them to know their rights and be able to defend them, educational institutions’ curricula are to encompass economic and financial matters (this applies to secondary‑school curricula and subjects). However, how the latter measure has been implemented and whether enough attention was paid to it are not very clear.

Secondly, the state should be active enough in its implementation of actions protecting the collective interests of consumers, especially the mechanism for controlling unfair commercial practices and the penalisation mechanism under the law implementing the Consumer Credit Directive.

Finally, if thorough analyses properly identify the problems in the consumer-credit market and prove that there are serious reasons and suitable justification for strict regulation measures, the state should ask itself how balance among the various interests should be achieved and what level of ‘average’ consumer the regulatory measures should target. This author at least is not convinced that the law should protect a consumer who does not want to exercise care himself.

3. Conclusions

Analysis of existing consumer-credit regulation in Lithuania reveals that, on one hand, even now there are some norms regulating the consumer-credit market that could protect the interests of consumers and prevent excessively easy access to non-secured consumer loans via electronic means—if applied effectively. On the other hand, there are some norms that remain unclear and that do not comply with the general provisions of civil law. Most of these norms’ practical application has not been tested; therefore, it is unclear what precisely is behind the ineffectiveness of these norms. It is also obvious that there has been no research into why certain legal norms do not reach their goals and what legal measures are most effective for resolving the issues specific to the consumer-credit market; i.e., it is not clear what particular market failure should be addressed and what regulatory measures might be adequate for the correction of such failure. The amendments to the Law on Consumer Credit that have been proposed by the supervisory institution, the Bank of Lithuania, imply that the national institutions see only one solution for the issues in the consumer-credit market—stricter (tighten) regulation—and in some cases specify drastic measures not only with respect to business but also with respect to consumers. In addition, the proposed amendments to the regulations pertaining to the consumer‑credit market clearly imply that the proposals have been made without comprehensive analysis of the legal consequences and, with the result that they are not worded properly from a legal point of view. This means that, although most of them will probably be incorporated into existing legislation, it is most likely that they will not reach their goals.