100 Years Later

29/2020

ISBN 978-9985-870-48-8

Issue

Insurer’s Duty to Obtain Information under the IDD Directive – Threat or Opportunity?

Enacting Directive 2016/97, on insurance distribution (the IDD), has, inter alia, extended the scope of application of regulation, increased the requirements for expertise of the personnel of insurers and insurance intermediaries, and particularised the content of the duty to give information. One of the novelties in the IDD, with regard to the insurer’s duty to provide information, is the duty of the insurer to obtain information from the customer for enabling fulfilment of its own duty to give information. Before the IDD, the balance between the insurer’s duty to give information and the customer’s duty to become acquainted with the information received was customarily understood in many legal systems such that the insurer is obligated to supply comprehensive information on its insurance products in an understandable form while the customer bears the risk of selecting correct and sufficient insurance in reliance on the information received. In other words, the insurer is liable in respect of the information as such, but the customers accept a risk of applying the information incorrectly in their specific circumstances.

This background gives rise to the following questions, examined in the article: 1) What is the legislative background of the new duty to obtain information, and what are the objectives behind it? 2) What are the consequences of neglecting this duty? 3) What is the ‘upside risk’ of the reform? That is, in what kinds of cases could the new duty improve matters? 4) What is the ‘downside risk’? In other words, might the new duty cause any problems?

The article provides analysis focused on the IDD itself rather than on any national jurisdiction in which the directive has been implemented.

Keywords:

Insurance law; Insurance Distribution Directive; duty to obtain information; duty to give information; mis-selling

1. Introduction

Directive *2 (EU) 2016/97 of the European Parliament and of the Council on insurance distribution (recast), (‘IDD’), came into force on 23 February 2016, and its transposition period expired on 1 October 2018. *3 The IDD substituted and repealed Directive 2002/92/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council on insurance mediation. Enacting the IDD, inter alia, extended the scope of application of regulation, elevated the requirements for personnel expertise within insurers and insurance intermediaries, and particularised the content of the duty to give information.

One of the reforms IDD brought about was that regulation of the duty to give information was extended to cover not only insurance intermediaries but also insurers themselves *4 – prior to IDD, regulation of the insurer’s duty to give information to a customer was left mostly to national legislators. A noteworthy element in the IDD rules concerning the insurer’s duty to give information is that the directive contains a detailed list of issues that must be notified to the customer (art 20(8) IDD). This legislative technique corresponds to that adopted in Directive 2009/138/EC on taking up and pursuing the business of Insurance and Reinsurance (Solvency II) in the field of life insurance (see art 185(3)) as well as that adopted in art 2:201 of the Principles of European Insurance Contract Law (‘PEICL’) as generally applicable. *5 On the other hand, this technique deviates from the one customarily utilised in Nordic countries, where the content of the insurer’s duty to give information has been defined with compact general clauses. *6

Another but not so obvious novelty in the IDD, as regards the insurer’s duty to give information, is the insurer’s duty to obtain information from the customer to be able to fulfil its own duty to give information. According to art 20(1) IDD, ‘[p]rior to the conclusion of an insurance contract, the insurance distributor shall specify, on the basis of information obtained from the customer, the demands and the needs of that customer and shall provide the customer with objective information about the insurance product in a comprehensible form to allow that customer to make an informed decision.’ *7 The duty to obtain information is even stressed in situations where the insurance distributor not only offers insurance contracts to be concluded but gives advice on insurance issues, that is, by providing ‘a personal recommendation to a customer, either upon their request or at the initiative of the insurance distributor, in respect of one or more insurance contracts’ (art 2(1)(15) IDD). *8 In the case of advising, ‘the insurance distributor shall provide the customer with a personalised recommendation explaining why a particular product would best meet the customer’s demands and needs’ (art 20(1) IDD). *9

In addition, the content of the insurer’s duty to obtain information is specified further in the context of insurance based investment products. In that situation an insurance intermediary or insurance undertaking must also obtain the necessary information regarding the customer’s knowledge and experience in the investment field as well as their financial situation and investment objectives as provided in more detail in art 30(1) IDD. The focus of this article is, however, on ‘normal’ insurance, not on insurance-based investment products.

An insurer’s duty to obtain information from their customer is unknown in previous EU legislation on insurance. *10 The same holds true as regards the PEICL – even though its second edition is newer (2016) than the directive proposal that later developed into the IDD. *11 Interestingly, however, the insurer’s duty to obtain information from the customer is not completely unknown in the PEICL, either, though the duty is limited to those circumstances of the customer that are more or less obvious to the insurer. According to art 2:202 PEICL, ‘ – – the insurer shall warn the applicant of any inconsistencies between the cover offered and the applicant’s requirements of which the insurer is or ought to be aware – – ‘. According to the commentary text, this ‘duty of assistance’ is limited ‘to situations where the insurer had reason to know about gaps in cover – – , because the actual risk situation of the applicant was apparent to the insurer or where such a gap should reasonably have been anticipated by the insurer’. *12 Thus, under the PEICL an insurer is obligated to warn a customer whose misunderstanding as to the content of the insurance cover is apparent, whereas in contrast the IDD includes an automatic duty to request information from the customer.

The absence of a duty to obtain information from the customer in the PEICL is not surprising because the balance between the insurer’s duty to give information and the customer’s duty to become acquainted with the information received is customarily understood in many legal systems, roughly speaking, so that (a) the insurer is obligated to give comprehensive information on its insurance products in an understandable form, but (b) the customer bears the risk of selecting correct and sufficient insurance relying on the information received. In other words, the insurer is liable in respect of the information as such, but the customer bears the risk of applying the information incorrectly in their own circumstances.

Another question is: what is the relationship between a) the insurer’s duty to obtain information under art 20(1) IDD and b) the applicant’s to duty to inform the insurer of circumstances which may be of importance for assessment of the insurer’s liability? The latter type of duty is not touched upon in the IDD but included in all European insurance contract acts *13 , art 2:101 PEICL as well as probably all other jurisdictions globally.

From a theoretical point of view the relationship between these two duties seems clear as they differ from each other both from the temporal perspective and in terms of their function: The insurer’s duty to obtain information precedes the applicant’s duty to give information as the function of the former is to enable the insurer to offer suitable types of insurance to the customer, *14 and once the correct insurance has been identified, then the applicant must provide the insurer with sufficient information to enable the insurer to calculate the risk and set the insurance premium. *15 However, from a practical point of view the functions of these two duties may be blended. For example, even if an insurer neglected its duty to obtain information from the customer, the information provided by the customer on their circumstances may reveal to the insurer that the insurance they initially selected is not suitable for the needs of the customer. However, in the present article the focus is on the insurer’s duty only – thus, the analysis is implicitly based on the assumption that the information to be subsequently provided by the customer as to their circumstances does not touch upon the same issues that are in the scope of the insurer’s duty to obtain information.

This background gives us a reason for the following research questions:

1) What is the legislative background of the new duty to obtain information, and what are its objectives?

2) What are the consequences of neglecting the duty?

3) What is the ‘upside risk’ of the reform, that is, in what kind of cases could the new duty improve things?

4) What is the ‘downside risk’, in other words, might the new duty cause any problems?

My analysis focuses on the IDD directive itself, not on any national jurisdiction where the directive has been implemented. For illustrative purposes, I use certain case examples from the complaints boards under the Finnish Financial Ombudsman Bureau. *16 However, my focus is on the facts of the cases, not on the Finnish legal provisions that were applied to them, so the analysis is intended to be understandable to any reader, irrespective of whether they know Finnish law or not.

I was the chairman in some of the board cases which are analysed below. Whenever this is the case, it is mentioned explicitly, for the sake of transparency.

2. The Legislative Background and Objectives of the Duty

The insurer’s duty to obtain information from a customer is touched upon only very lightly in the preamble of the IDD. Paragraph 44 states that ‘[i]n order to avoid cases of mis-selling, the sale of insurance products should always be accompanied by a demands-and-needs test on the basis of information obtained from the customer’. Then it adds that ‘[a]ny insurance product proposed to the customer should always be consistent with the customer’s demands and needs and be presented in a comprehensible form to allow that customer to make an informed decision’. The brevity of the reasoning of the new duty is slightly surprising taking into account that the new duty meant, as noted above, at least a small-scale paradigm shift in the relationship between insurer and its customer.

Another issue is that from the European legislator’s viewpoint the paradigm shift perhaps has not appeared as significant in practice as it is from a purely legal perspective. As noted above, Directive 2002/92/EC on insurance mediation already contained a corresponding duty in the relationship between the intermediary and the customer (art 12(3)). The structures of insurance distribution vary significantly between different Member States, and in many of them direct sales between insurers and customers represent only a small minority of all sales. *17 From the viewpoint of such Member States, extending the scope of application of the duty to obtain information from intermediaries to insurers has perhaps not appeared as particularly significant.

That said, the background of the duty to obtain information becomes clearer when looking at the proposal for the directive. The duty to obtain information is present in both in the context of ‘normal’ insurance as well as insurance-based investment products. *18 However, in the preamble the duty is discussed only in the context of insurance-based investment products. *19 Furthermore, the general part of the preamble mentions that the planned directive should, ‘whenever the regulation of selling practices of life insurance products with investment elements is concerned, – – meet the same consumer protection standards as MiFID II’, that is, the revised directive on markets in financial instruments. *20 Later the preamble adds that ‘[s]ome parts of the new Directive will be reinforced by Level 2 measures in order to align the rules with MiFID: in particular, in the chapter regulating the distribution of life insurance policies with investment elements’. *21

Thus, it seems that the logic of the European legislator has been the following: first, regulation on issuing insurance-based investment products must be harmonised to meet the standards of providing normal investment products and investment services; *22 second, regulation of ‘normal’ insurance must be harmonised with regulation of insurance-based investments.

The duty of a service provider to obtain information from its customer has a long history in the context of investment services. The EU legislator has obliged a provider of investment services to obtain information from its customer since the very first directive in this field: Directive 93/22/EEC on investment services in the securities field. According to art 11(1), ‘an investment firm – – seeks from its clients information regarding their financial situations, investment experience and objectives as regards the services requested’. A corresponding duty was enacted in the successor to this directive, in the shape of Directive 2004/39/EC on markets in financial instruments (‘MiFID’), yet in a significantly more sophisticated form, in art 19(4)–(6) of the said directive. The duty is present, of course, in the current directive in force in that field: Directive 2014/65/EU on markets in financial instruments (’MiFID II’) in art 25(2)–(4).

As we have seen, the objective of the duty to obtain information is, according to the preamble to the IDD, to ‘avoid cases of mis-selling’. In the insurance branch, the concept of mis-selling is understood as meaning a situation where a customer is sold a product that is not suitable for them. *23 The implications of mis-selling may be divided to positive and negative sides: 1) the customer pays for insurance cover they do not need (positive side); 2) the customer is not covered by their insurance against a certain risk that they themselves understand as being covered (negative side). *24 The positive implication is not normally a major problem for a customer in the short run but accumulates unnecessary costs in the long run. The negative implication, on the other hand, may even be beneficial for the customer until the non-covered risk materialises, because the insurance premium may be lower than it would have been had the unintentionally non-covered risk been within the sphere of the insurance. However, if the risk materialises, the (negative) consequences may be drastic for the customer.

3. Consequences for Neglecting the Duty to Obtain Information

In the previous section, we saw that the main objective of the new duty to obtain information is to avoid cases of mis-selling. The next question is: How does the duty to obtain information actually help to avoid these situations, or tackle their consequences? One may rise factual, remedial and procedural aspects. From a factual viewpoint, it seems plausible that if insurers’ representatives obtain information about their customers’ circumstances and insurance needs, this enhances their possibility to offer suitable insurance to the customer as well as helping them to focus on relevant issues when giving information about insurance.

From the remedial viewpoint, the first question is what the remedies for non-compliance with the duty to obtain information from a customer are. As is normal with EU legislation, the IDD itself contains no provisions on civil law remedies for non-compliance with directive-based national legislation; rather, remedies are left to be determined by national legislation. *25 Thus, the character and content of remedies for non-compliance with the duty to obtain information may vary between Member States depending on legislation on insurance contracts as well as the general rules and principles of civil law in each country.

In this article is neither possible nor functional to analyse the question of remedies in different legal systems. However, I would surmise that most legal systems have no direct civil law remedy for non-compliance with the duty to give information. This is because even in the IDD the duty does not serve the customer’s interest directly, but only indirectly through the insurer’s duty to give information about insurance offered. To be more precise, the function seems to be as follows: Under the IDD, the extent and content of the insurer’s duty to give information is determined assuming that the insurer has obtained necessary information from its customer. From this point of view it is irrelevant whether the insurer has actually fulfilled its duty to obtain information or not. Either way, it is regarded as having neglected its duty to give information if it has not given its customer the information that it would have given had it requested information from its customer and otherwise acted reasonably. Thus, at least the IDD itself does not assume legal orders to provide direct legal remedies to enforce the duty to obtain information. Rather, the consequences of failure to comply with the duty are, by default, determined indirectly through remedies for failure to give appropriate information. *26

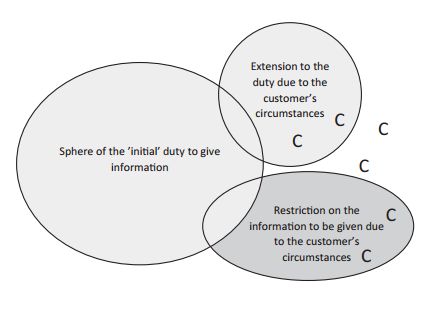

It must be emphasised that the duty to obtain information cannot only extend the amount of information that the insurer must give to its customer but can also limit it. The latter happens in a situation where the information obtained from the customer reveals – or, if it had been obtained, it would have revealed – to the insurer that certain insurance is not suitable for the customer because of some special circumstances of the customer, and because of this, that particular insurance should not be recommended to the customer. *27 This situation is more typical in the context of insurance-based investments than ‘normal’ insurance, though in principle it may also occur in the latter context.

The idea may be illustrated with a drawing, where the C’s stand for different circumstances of the customer, and the combined area of the two light grey ellipses represents the sphere of all the information that the insurer is obliged to give its customer, reduced by the dark grey area representing information or recommendation that should not be given to the customer.

In the IDD the question of remedies for non-compliance with the duty to give information to a customer is also left to be determined in national legal orders. Remedies available to a customer in such a situation might include, depending on the legal system, a right to declare the insurance contract void or terminated, a right to damages, or a right to modification of the insurance contract in accordance with their reasonable expectations. *28 The latter remedy may occur either by virtue of a special provision in the (national) insurance contract act, *29 or on the grounds of general rules and principles of interpretation of contracts. *30

One can even recognise a procedural aspect in relation to the duty to obtain information. In cases where it is disputed whether the insurer has given appropriate information to the customer or not, the evidence is quite often imperfect on both sides. For example, the insurer may allege that its representative has notified the customer of a certain essential limitation in the insurance cover, whereas the customer denies this, but either side has no evidence to support their standing. If in that situation it is established that the insurer has neglected its duty to obtain information from the customer, this omission may have certain significance as an indicator favouring the conclusion that the duty to give information has also been neglected. This is because when the purpose of the duty to obtain information is to support fulfilment of the duty to give information, failure to fulfil the former may indicate – at least in dubious case – omission of the latter. However, this is not a ‘real’ remedy for neglecting the duty to obtain information but just a possible line of reasoning when a judge is assessing the evidence in an individual case.

4. Case Examples

4.1 Introduction

The question of the significance of the insurer’s duty to obtain information from the customer is next approached through case examples from complaints boards under the Finnish Financial Ombudsman Bureau. Because of the novelty of the insurer’s duty to obtain information, there are as yet no case examples directly concerning the duty. However, two groups of cases are worth analysing here because they may give an indirect clue as to what the consequences of the new duty might be.

First, we focus on a few cases from the Insurance Complaints Board (‘ICB’) from the era prior to enactment of the duty to obtain information. These cases share two elements in common: 1) they include an element of mis-selling, in that the insured believed themselves as being covered by their insurance from a certain risk, but according to the policy terms that was not the case; 2) the (then) provisions of the insurance contract act left the consequences to be borne by the insurer. Thus, my purpose is to present examples of real scenarios in which the duty to obtain information from the customer could have helped the insured to be covered against a risk that they believed has been covered.

Second, we focus on certain cases from the Securities Complaints Board (‘SCB’; now known as the Investment Complaints Board), in which a service provider’s duty to obtain information from its customer became relevant in the decision of the case. As mentioned in section 2 above, the service provider’s duty to obtain information from its customer has been a part of regulation of investment services since the 1990s. The purpose of presenting and analysing the selected securities cases is to illustrate the circumstances when the duty to obtain information may become significant and how it can affect the outcome of the case.

4.2 Insurance Cases

Our first case example from the ICB is the resolution recommendation VKL 266/16 (2017). *31 In this case, an accounting office had, when providing services to its customer, accepted a commission to file an application for a title registration. However, the application had been filed too late, which had rendered the client liable to a penal tax of 16,000 euros. The office sought compensation from its liability insurer. The application was denied, because the insurance had been granted to cover only provision of accountancy and audit services as well as consultation in tax and company matters. According to the insurer, a commission to apply for a title registration is a task relating to the real estate business. The office took the case to the ICB alleging its ill-fated application as belonging to the insured line of business. According to the office, applying for title registration is a typical task when providing financial administration services especially if the customer is a firm in the building trade.

The ICB dismissed the complaint, accepting the insurer’s reasoning that applying for a title registration is, as a legal measure, by its nature a measure belonging to the law of real estate. The ICB also noted that even though the legal consequence of a delayed application was a penal tax, this did not change the nature of the measure itself to be (or become) tax law, that is, a legal context that was within the sphere of the insurance. Thus, the loss-causing measure was held as not being covered by the insurance.

The case and the ICB’s decision were quite straightforward because the office had not even alleged that it would not have received proper information about the insurance. The office’s only allegation was that the policy term defining the lines of business that are covered by the insurance must be interpreted as including a situation where the office applied for a title registration as part of other financial administration services. Thus, from a legal point of view, the case concerned only interpretation of a contract, so that the insurer’s duty to give information did not become an issue. However, in its straightforwardness the case is a clear-cut example of a situation in which the course of events could have been quite different had the insurer been obliged to find out the nature of the insured business. Had the insurer realised that the insured occasionally applied for title registration in the name of its customers, it would have been easy to extend the sphere of insured events to cover these kind of measures – for a higher premium, of course.

Next, the resolution recommendation VKL 747/04 (2005) offers an example of situation where it seems quite clear that if the insurer at that time had a duty to obtain information from its customer, this would have affected the insurer’s duty to give information in the circumstances of the case. In this case, a holiday rental cottage had been damaged by fire. The owners of the cottage, who had so-called extended home insurance for the cottage, sought compensation for, inter alia, loss of rental revenues. The insurer denied the application as far as rental revenues were concerned, stating that according to the insurance policy, loss of rental revenues was not covered by the terms of insurance.

The owners took the case to the ICB stating that in their oral discussion they had told the insurer’s representative that the cottage was in rental use. Compensability of rental revenues was of utmost importance to the owners because they had purchased the cottage on loan, thus planning to pay the instalments with the rental revenues. Because the insurer’s representative had not informed the owners of exclusion of rental revenues, the insurer had neglected its duty to give information on insurance policies and essential limitations to the insurance cover, as required in the Insurance Contract Act. The insurer, on the other hand, contested the allegation that rental use of the cottage had been discussed when the insurance contract was concluded.

The ICB found it unclear what had actually been discussed when the contract was concluded. Thus, the owners had failed to prove having received wrongful information about the insurance policy. The ICB rejected the complaint.

The ICB did not take a stand explicitly on the question whether the clause precluding compensation of lost rental revenues could be regarded as being an essential restriction to insurance cover to which the insurer would have had a duty to pay attention when concluding the insurance contract. Clearly, the answer was understood as being negative at least if the owners had not mentioned the rental use of the cottage – otherwise the insurer should have been able to show they had notified the clause to the owners. In any case, it seems probable that if the insurer had had a duty to obtain information in those circumstances, then the insurer should have received information about the rental use, and in that case the insurer quite clearly should have paid attention to the critical limitation clause in the insurance policy.

4.3 Securities Cases

Next, we analyse two SCB cases in which the duty of a service provider to obtain information from its customer became significant in a situation where the customer purchased an unsuitable investment product. As noted above, the purpose of this analysis is to provide a point of comparison and thus shed light on the significance of the corresponding duty in the context of an insurance contract.

Our first example is case APL 621/02 (2002). The facts were that a bank had contacted two siblings recommending that they sell a part of listed stocks they had received as an inheritance about 20 years earlier, and put the money in a bond issued by the bank as well as in mutual funds managed by a company from the same company group as the bank. The siblings had followed the recommendation. Realization of the increase in value of the stocks had rendered the siblings liable to pay tax for the capital gain. In addition, the State Study Grants Centre had taken the capital income into account when determining the student financial aid for each of the siblings, which had decreased the aid they received. The siblings claimed compensation from the bank alleging that they had been totally inexperienced in managing investments and thus unaware of its fiscal effects as well as the effect on student financial aid.

The SCB stated that normally even private persons may be required to understand that selling assets may cause fiscal consequences. However, the SCP noted that in this case it had been the bank that took the initiative in the case and recommended realisation of the stocks, even though it was aware of the siblings’ lack of experience of investment. In these circumstances, the bank should, according to SCB, have paid attention to fiscal issues when recommending the transaction so that the siblings could have assessed the fiscal questions and perhaps seek further information on the issue. According to the SCB, the same held true as regards student financial aid, which is one of the most common forms of welfare aid in Finland. Thus, the bank was held as having failed to give sufficient information to the siblings.

The case is a clear-cut example of how a service provider’s duty to obtain information from its customer may affect the content of the duty to give information to the customer. Even though explaining fiscal and social security issues was not regarded as belonging to the scope of the duty to give information in its ‘normal’ form, notifying customers of these issues became necessary because of the circumstances of the case and the customers. Thus, in this case the duty to obtain information had an extensive effect on the scope of the duty to give information.

Another, slightly more complicated but perhaps even more interesting example of the significance of the duty to obtain information, is case APL 12/13 (2014). *32 In this case, C Ltd. had concluded an interest swap agreement with a bank. According to the agreement, C was obliged to pay interest in a certain sum at a flexible rate based on the consumer price index whereas the bank was obliged to pay interest on a flexible rate based on the difference between the Euribor 6 months’ reference rate and a fixed marginal. The fixed contract period was ten years. After concluding the contract, the real interest rate decreased significantly, which led C’s position to become highly unprofitable. Two years after conclusion of the agreement the parties agreed to cancel it, but according to a mechanism described in the swap agreement, the bank was entitled to a lump payment of MEUR 1.55 from C.

C took the case to the SCB alleging that the swap agreement was unsuitable for it and that it had not been properly informed of the risks of the investment. According to the bank, it had obtained relevant information on C’s financial position and investment objectives in accordance with the regulation in force, both when C’s customer relationship was established and again prior to offering the swap agreement to C. According to the bank, C was an experienced investor who sought significant returns against high risk.

The SCB noted that the bank had not presented any evidence for its allegation of having obtained information about C’s investment objectives and C’s financial position – even though the bank was, according to the regulation in force, obliged to store the documentation on information it had obtained from the customer concerning their circumstances. Thus, the SCB held the bank as having failed to show it had obtained the required information from the customer. Furthermore, because the bank did not have the required information on C’s circumstances, it should not have recommended such a risky investment – as indeed the swap agreement was. In addition, the bank was found as having provided false information when its representative in a phone discussion had denied the possibility that reference rates could ever become negative – a fairly typical opinion at that time (2009). Thus, the bank was held liable in the sum of MEUR 1.125, which represented most of C’s loss. The rest of C’s loss was left to be borne by C itself, because it was found to have delayed cancelling the agreement and thus failed to mitigate its loss.

The case underlines the formal significance of the duty to obtain information – and the significance of evidence on fulfilment of the duty. It remained unclear until the end why the bank actually had recommended the swap agreement to C, and the merits on which C had assessed the agreement to be beneficial to it. Credit swap agreements may play an important role in the financing strategy of a business *33 having, for example, significant loans at a flexible interest rate or long maturity receivables at nominal value, and thus vulnerable to inflation. In such situations, interest swap agreements – if concluded and managed with skill and care – may help the business to protect its position against inflation or disadvantageous changes in the reference interest rate applicable to its loans. In the case at hand, however, C had not had such loans or receivables leading to the idea to purchase protection through a credit swap agreement. Moreover, the nominal capital of the swap agreement was significantly large compared to C’s balance sheet.

Because of these circumstances, according to the SCB, the bank should not have recommended the swap agreement to C. This led the bank to be held liable for most of the loss – together with the aforementioned incautious prognostication on development of reference rates. The bank was not saved by the fact that the ‘main’ information it had given to its customer, including exact documentation and a brochure about the swap agreement, was found as such appropriate by the SCB. Thus, the case clearly illustrates the potential effect that the duty to obtain information may have on a service provider’s duty to give information: because of the circumstances of the case, giving neutral information and recommending the swap agreement was held as amounting to negligence. In other words, in this case the duty to obtain information had a restrictive effect on providing information from the bank to its customer.

5. Possible Problems

As we have seen, the duty to give information most likely has positive effects on the relationship between the insurer and its customer. First, it presumably de facto helps the parties to avoid situations where the customer would purchase an unsuitable insurance. Second, it shifts the risk of negative consequences of mis-selling insurance a step towards the insurer, and thus improves customer protection in such cases. Does the duty to obtain information have negative effects, too?

One potential problem is the possibility that obtaining information from a customer becomes more or less a formality in a way that neither insurers nor customers put too much effort into monitoring and analysing the customer’s circumstances. If this happens, the duty to obtain information does not achieve its goals, but may cause unnecessary transaction costs. It is even possible that sloppy surveys on a customer’s circumstances will become, as pieces of evidence, merely misleading and thus distort the picture of the case in later proceedings before a court or complaints board. This problem has sometimes been faced by the SCB, especially in a recent group of related cases. Many of these cases shared the common feature that customers who were according to their own words risk-averse, had signed filled-in forms assuring, inter alia, the customers’ knowledge of derivatives as well as their willingness to seek high returns for high risk. The SCB held that because of similar stories from many independent customers, their allegation that they had been misled into signing the forms was plausible, so that the forms were not given any value as evidence. *34 However, in the vast majority of cases before the SCB no such problem has occurred, but the parties seem to have fulfilled their responsibilities on monitoring the circumstances diligently and bona fide.

Another question is whether the duty to obtain information from the customer becomes a ‘dispute generator’, that is, a legal vehicle on which customers try to ride in almost any case where they have not received compensation for their loss from their insurer. It is possible that the new duty may cause a certain number of disputes at least during the early years, but it is difficult to see that this would become a significant phenomenon in the bigger picture. From a larger perspective, insurance disputes with an element of mis-sale are quite rare. In a clear majority of disputes, the customer has selected the most suitable of the insurance products offered, even though it may happen that the customer does not get all of their losses compensated from the insurance. The significance of the insurer’s duty to obtain information from the customer is remote in most of such cases.

In addition, one may ask whether the insurer’s duty to obtain information enables situations where a minor and excusable failure to fulfil the duty – or merely inability to show fulfilment – leads to insurer’s liability for loss which has never really been understood by the insured to be covered by the insurance. In other words, does the duty create a risk of the insured benefiting unjustifiably from the insurer’s mistake, which is, more or less, of a merely formal nature? The risk is emphasised because of the relative complexity and particularity of the duties to provide information under the IDD. *35 One may see such risk in circumstances resembling those of the above analysed resolution recommendation APL 12/13 (2014) concerning the bank’s recommendation to a customer to conclude a swap agreement. In that case, it was undisputed that the bank de facto had known its customer for a quite long time. The bank also alleged that it had monitored the customer’s investment objectives, but it was not able to show any documentation on this. For that reason, plus an incautious prognostication on the phone on development of reference rates, the bank was held liable for most of the customer’s loss. One may also note that it was undisputed that the customer was an experienced and successful investor.

Such outcomes may appear as being harsh from the insurer’s viewpoint. This risk may also lead insurance distributors to engage in defensive selling practices, that is, recommending more insurance than is needed, in order to avoid professional liability claims. *36 On the other hand, insurers are always quite large corporations, for whom it should not be unreasonably burdensome to be obliged to keep comprehensive documentation on essential parts of communication with customers, and otherwise be able to follow more or less strict patterns in their conduct. It is also worth noting that cases such as APL 12/13 (2014) are, in my experience, exceptional. In the vast majority of cases, banks and insurers diligently follow different rules of conduct. Thus, one may ask whether even though formal rules of conduct, such as the duty to obtain information, would lead in some, but still quite rare, cases to harsh outcomes from the insurer’s viewpoint, such rules are justifiable by their benefits for the body of customers. Furthermore, a high level of customer protection improves the reputation of the insurance industry and thus benefits insurers, too. *37

6. Conclusions

The insurer’s duty to obtain information from its customer is an interesting addition to regulation on the relationship between an insurer and its customer. As has emerged above, such a duty does not create – at least the IDD does not require it to create – any direct rights for the customer, but, rather, the effect of the duty materialises indirectly through the insurer’s duty to give information to its customer. The effect is the following: the extent and content of the insurer’s duty to give information is determined assuming that the insurer has obtained necessary information from its customer. If the information then given by the insurer does not meet the requirements which were defined in the aforementioned way, the consequences of neglecting the duty to give information to the customer are determined according to national rules on insurance and contract law.

The case examples analysed above indicate that the duty to obtain information may in certain, yet in practice quite rare, circumstances have a strong effect on how the negative consequences of mis-selling insurance affect the parties. This improves customer protection but perhaps sometimes raises the question whether the customer may also stand to gain an unjustified benefit at the cost of the insurer. Such an outcome would occur if a customer obtains insurance compensation because of the occurrence of a risk that the customer in reality never believed to be covered by the insurance. However, my conclusion is that even though such an outcome is possible in certain quite exceptional situations, the practical significance of this problem is minor balanced against the benefits to customer protection in cases of mis-selling insurance, where the customer’s situation has until now often been quite problematic.

pp.23-33